A palaeontologist, a medical pathologist, and an orthopaedic surgeon walk into a museum. No, it's not the start of a joke, but the research team that has now diagnosed the first confirmed case of aggressive bone cancer in a dinosaur.

The specimen in question is a fossilised shin bone from Centrosaurus apertus, a plant-eating horned dinosaur that lived and died roughly 76 million years ago.

What looked - at least on first impression - like a poorly healed fracture turned out to be a tumour engrossing the upper half of the animal's shin bone, or fibula. The centrosaurus was diagnosed with an osteosarcoma; it's the most common type of bone cancer in humans, but marks the first confirmed case of any malignant cancer we've found in a dinosaur.

"Here, we show the unmistakable signature of advanced bone cancer in [a] 76-million-year-old horned dinosaur – the first of its kind," said pathologist Mark Crowther. "It's very exciting."

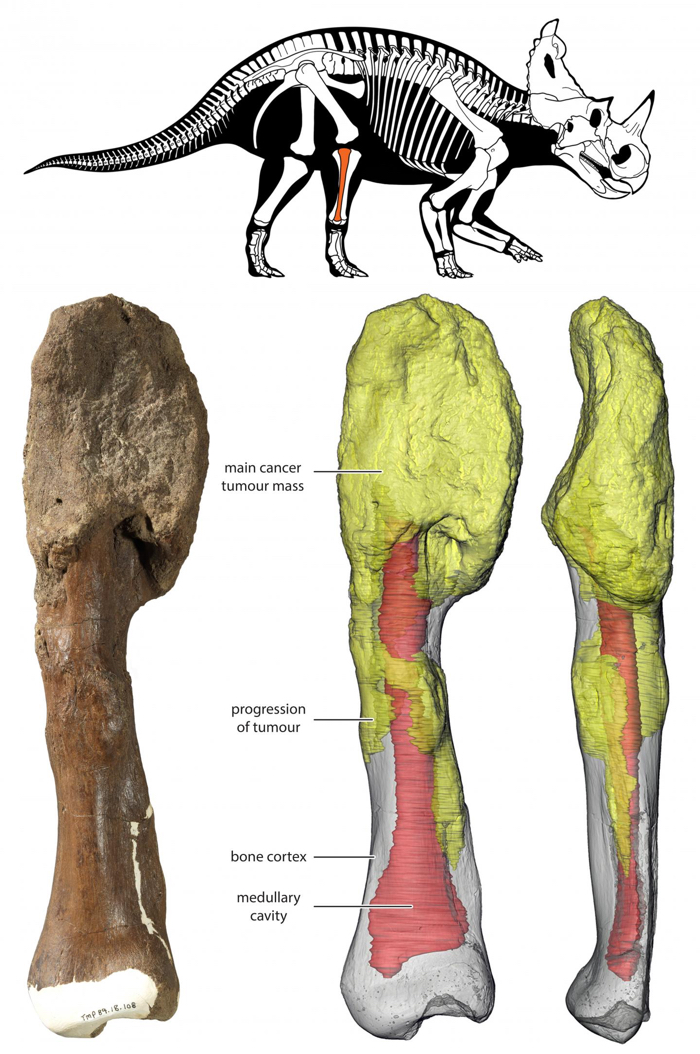

The shin bone, with the main tumour mass in yellow. (Danielle Dufault/Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)

In humans, osteosarcomas often affect growth-spurting teenagers and young adults. If an osteosarcoma metastasises - grows beyond the bone - it most often spreads to the lungs, but can also form tumours in other bones, and even the brain.

However curious we are about the evolution of diseases such as cancer, soft tissues like tendons, ligaments, bone marrow and tumours, are rarely preserved in fossils. Given a few years – let alone a million – these tissues would decay. So even if dinosaurs were regularly struck down by cancer, any diagnostic samples are going to be hard to find.

Scientists have come across similar cancer-like symptoms on dinosaur fossils before. Unusual lesions in the tail vertebrae of a young hadrosaur resembled a condition called Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a complex cancer which leaves room for debate over its manifestation. In the case of this most recent discovery, the malignancy is far more clear.

The cancer-stricken fossilised shin bone of C. apertus was unearthed in Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, Canada back in 1989, and had been stored at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, outside of Calgary, until its recent reanalysis.

Cross sections of the C. apertus bone were taken first with a CT scanner, the same machine used to identify bone fractures and tumours in people. The X-ray image 'slices' were reconstructed to see how the tumour grew through the fossilised bone.

In fact, it had spread through the bone quite extensively, which the team of medical specialists took as a sign that this centrosaur lived with its cancer for quite some time.

Artist's impression of Centrosaurus apertus. (Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)

Artist's impression of Centrosaurus apertus. (Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)"This discovery reminds us of the common biological links throughout the animal kingdom and reinforces the theory that osteosarcoma tends to affect bones when and where they are growing most rapidly," said Seper Ekhtiari, an orthopaedic surgeon-in-training at McMaster University in Toronto, who examined the fossil.

As the cancer was so advanced, the researchers think it might have spread to other parts of the dinosaur's body, but we don't have any of those tissue samples - such as the spongy lungs - from this ancient animal to make sure.

"The shin bone shows aggressive cancer at an advanced stage," said paleontologist David Evans. "The cancer would have had crippling effects on the individual and made it very vulnerable to the formidable tyrannosaur predators of the time."

After imaging the cancerous shin bone, thin sections were carefully sliced off the fossil and compared to a normal C. apertus fibula, along with one case of human osteosarcoma, from a 19-year-old man who had it in his lower leg.

In their paper, the authors note that "a similarly advanced osteosarcoma in a human patient, left untreated, would certainly be fatal."

But they suspect the dinosaur died with its herd mates, possibly in a sudden flood event, because the fossil was found in a massive bed of Centrosaurus bones.

"The fact that this plant-eating dinosaur lived in a large, protective herd may have allowed it to survive longer than it normally would have with such a devastating disease," Evans said.

And when we often marvel at the age of dinosaurs and their size, big and small, this latest medical discovery brings the plight of the dinosaurs a little closer to home.

"Evidence suggests that malignancies, including bone cancers, are rooted quite deeply in the evolutionary history of organisms," the authors concluded. Yes, even dinosaurs.

No comments:

Post a Comment