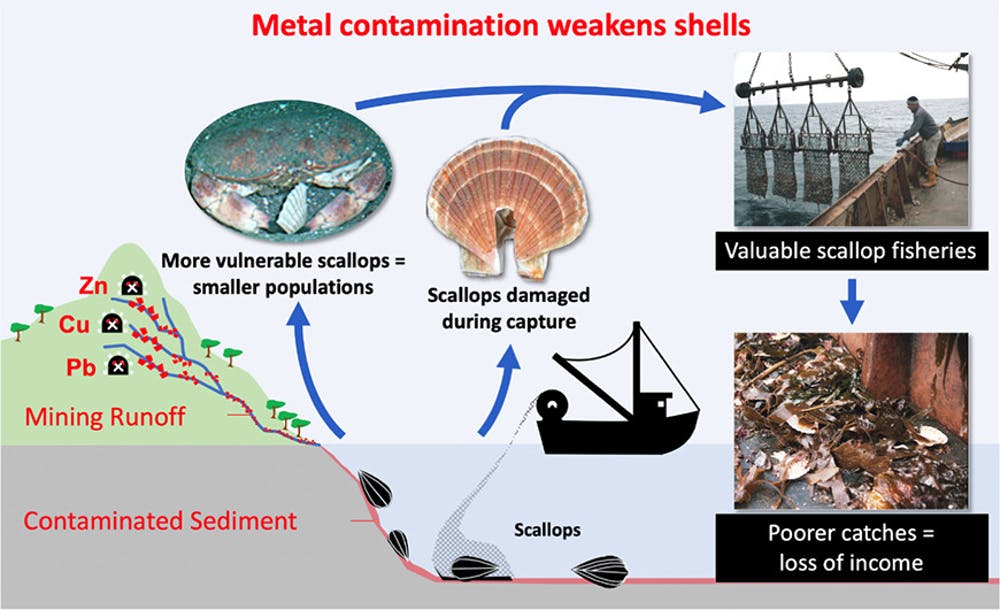

Shellfish like scallops, mussels, and oysters – bivalve mollusks – readily take up tiny specs of metals into their tissues and shells. Insufficient concentrations, this could harm their growth and survival chances, and even threaten the health of any human who eats their contaminated meat.

Such shellfish provide one-quarter of the world's seafood, therefore the impact of pollution from "heavy metals" like lead, zinc, and copper, is hugely important.

We recently investigated the consequences of metal pollution on the good scallop, Pecten Maximus, for a replacement scientific study. this is often a typical species that support the foremost valuable fishery in England and therefore the third most dear within the UK overall.

We first discovered these effects of pollution out of the blue. While closing routine stock assessment surveys round the Isle of Man, a self-governing island that lies between Britain and Ireland, we noticed that scallops found on the Laxey fishing ground off the geographic area were far more likely to possess lethally damaged shells than scallops from elsewhere.

Laxey is legendary for the world's largest working waterwheel, a spectacular example of Victorian engineering accustomed pump water from a mine which produced lead, copper, silver, and zinc.

The mine closed in 1929, but its legacy is that sediments within the rivers, estuary, and sea waters around Laxey are unnaturally high in metals.

It looked as if metal pollution could also be liable for the damaged shells we discovered. to check this hypothesis, we analyzed the strength of scallop shells that had been collected from Laxey and other fishing grounds around the Isle in both 2004 and 2013.

In both groups, the shells from Laxey were found to be significantly weaker than those from all other areas.

A detailed analysis revealed the Laxey shells were proportionally thinner than shells found in other areas, in which the interior structure of shells contained an interruption or line.

We weren't ready to detect metals within the shells themselves, but we expect that even in low quantities the metals are either affecting the physiology of the scallops or disrupting chemical reactions during the mineralization (shell-growing) process.

Scallops with unnaturally thin shells are also more likely to be damaged when being captured. (Stewart et al., Science of The Total Environment, 2020)

Scallops with unnaturally thin shells are also more likely to be damaged when being captured. (Stewart et al., Science of The Total Environment, 2020)

In ecotoxicology terms, what we observed is termed a non-apical endpoint effect. Weakened shells don't directly kill scallops, but instead, leave them more at risk of mortality.

Such responses are rarely considered when assessing the consequences of environmental contaminants but could have significant implications.

This is a priority because the amount of metal contamination we observed was generally below the present regulatory limits thought to affect marine life, and therefore the scallops were considered perfectly safe to eat.

Metals embarrassed

It is remarkable that mining from 100 years ago continues to be affecting marine life in this way.

But, only if metal contamination may be a common and increasing threat in coastal areas around the world, which many other shellfish and marine species like corals produce calcified structures chemically-similar to scallop shells, we believe metals are also having unseen effects on an outsized scale.

We may therefore have to rethink how we assess and manage the risks of metal contamination.

King scallops showing different levels of damage. (Bryce Stewart)

King scallops showing different levels of damage. (Bryce Stewart)

Metals are a natural component of marine systems and trace, concentrations is also essential for supporting life. However, human activities have elevated their concentrations in many marine environments to the purpose where they need to become toxic.

This pollution comes from a range of sources like a getaway from mining, agricultural and industrial activity; offshore oil and gas exploitation; and leaching of anti-fouling paint from ships hulls. As a result, metal pollution tends to be highest in estuaries, around ports, and in inshore waters.

Despite stricter recent regulations controlling the utilization of metals in marine environments, they still are an increasing threat. this can be because heavy metals are highly persistent (they don't disappear over time) and ongoing coastal development and bottom-towed fishing rig are remobilizing contaminated sediments.

Climate change is additionally exacerbating the threat because higher rainfall is increasing run-off from contaminated areas, and ocean warming and acidification is increasing the speed of uptake and toxicity of metals in seawater.

Most previous studies have to target the direct effects of metals on shellfish survival or food safety. However, our new study has unearthed that even relatively low concentrations of metal contamination appear to be causing scallops to grow weaker shells.

This leaves the scallops more liable to being eaten by crabs and lobsters and to disturbance from storms and fishing activity, with potentially substantial ecological and economic repercussions. The Conversation

Bryce Stewart, Senior Lecturer in Marine Ecosystem Management, University of York and Roland Kröger, Professor, Department of Physics, University of York.

No comments:

Post a Comment