Two ancient mummies discovered in an exceedingly rock-cut tomb in Egypt over 400 years ago are finally spilling their secrets, now that scientists have CT scanned their remains, a replacement study finds.

Both mummies, moreover as a 3rd on display in Egypt, represent the sole known surviving 'stucco-shrouded portrait mummies', from Saqqara, an ancient Egyptian necropolis.

Unlike other mummies, who were buried in coffins, these individuals were placed on wooden boards, wrapped in an exceedingly textile and a "beautiful mummy shroud", and decorated with 3D plaster, gold, and a whole-body portrait, said study lead researcher Stephanie Zesch, a physical anthropologist and Egyptologist at the German Mummy Project at Reiss Engelhorn Museum in Mannheim, Germany.

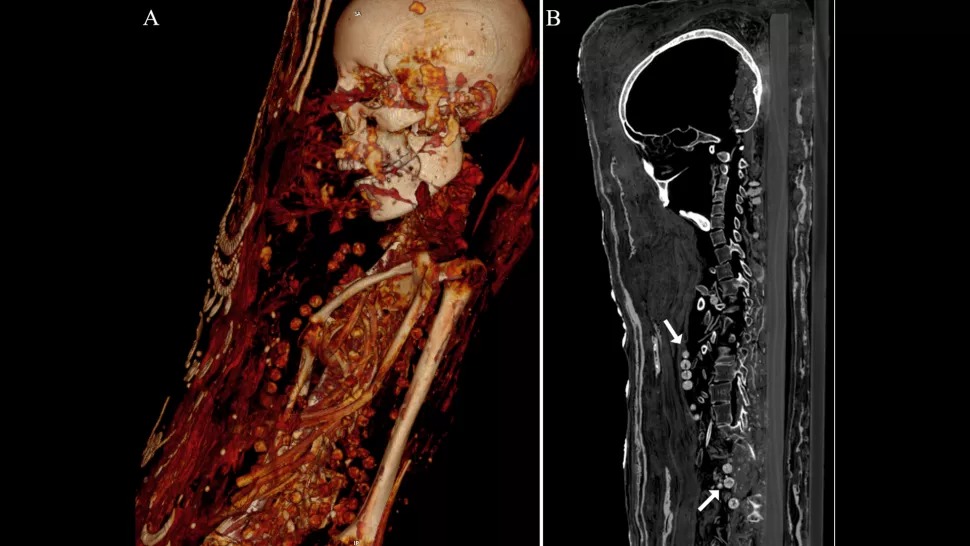

The CT scan showed the beads from the necklace around the woman's neck and body. (Zesch et al., PLOS One, 2020)

The CT scan showed the beads from the necklace around the woman's neck and body. (Zesch et al., PLOS One, 2020)

Now, CT (computed tomography) scans reveal that a minimum of one amongst these three stucco-shrouded portrait mummies was buried with organs (even the brain) which the 2 females were interred with beautiful necklaces, the researchers found.

The CT scans also showed that after the deaths of those individuals - a person, woman, and teenage girl dating to the late Roman period (30 BCE to CE 395) - their mummies were interred with artifacts likely thought useful within the afterlife, including coins that were possibly meant to pay Charon, the Roman, and immortal thought to hold souls across the river.

The CT scans also revealed several medical problems, including arthritis within the woman.

"The examination of the individuals yielded that they died at rather young ages … however, the reason for the death of the individuals couldn't be determined," Zesch told Live Science.

Long journey

Two of those mummies have traveled far and wide. In 1615, Pietro Della Valle (1586−1652), an Italian composer, took a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and ended up traveling through Egypt.

He learned about two stucco-shrouded portrait mummies - a person and woman - discovered by locals in Saqqara. Della Valle acquired these mummies and brought them to Rome, making them the "earliest samples of portrait mummies to possess become known in Europe," the researchers wrote within the study.

After passing through several owners, and a touch worse for wear, the mummies ended up within the Dresden State Art Collections in Germany, where they were X-rayed within the late 1980s. However, the CT scan revealed far more about their insides.

The teenager's mummy portrait. (Zesch et al., PLOS One, 2020)

The teenager's mummy portrait. (Zesch et al., PLOS One, 2020)

For instance, the CT scan revealed that the male died between the ages of 25 and 30. He stood about 5'4" inches (163 centimeters) tall and had two unerupted permanent teeth and several other cavities.

Some of his bones were broken and jumbled, probably because someone unwrapped him shortly after the mummy's discovery, the researchers wrote within the study.

While the man's brain wasn't preserved, there is not any evidence it had been removed through his nose. Nor were many embalming substances used. Instead, he was bound up and painted.

Two metal objects found during the CT scan are likely seals from the mummification workshop that handled his remains, Zesch said.

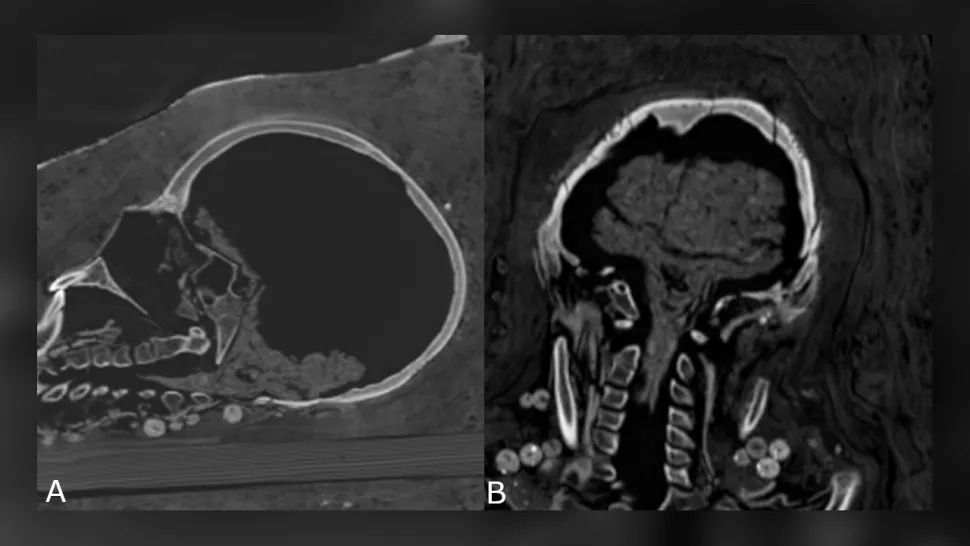

The teenager's shrunken brain. (Zesch et al., PLOS One, 2020)

The teenager's shrunken brain. (Zesch et al., PLOS One, 2020)

The woman's brain wasn't preserved either, but the teenagers was - it had shrunk, but the cerebrum and brainstem were still identifiable - and therefore the teenager's other internal organs were also present.

"We are quite sure there was no removing the brain or the inner organs" from these mummies, Zesch said.

"It's very probable that those mummies were only preserved due to a sort of dehydration with the utilization of [the desiccation mixture] natron, but there's not an enormous amount of embalming liquids."

The woman, who died between the ages of 30 and 40, stood about 4'11" (151 cm) tall. She had advanced arthritis in her left knee. The teenager, who wore a hairpin, in keeping with the CT scan, died between the ages of 17 and 19, and stood about 5'1" (156 cm) tall.

She had a tumor in her spine called a vertebral hemangioma, which is more common in people over 40, the researchers said.

Both women were buried with multiple necklaces. It's exciting to determine these necklaces, but it is not unexpected, Zesch said. "Because of those very precious shrouds, we are sure that those individuals need to be members of the upper socioeconomic class," meaning that they may have easily afforded jewelry, Zesch said.

Zesch noted that she studied the three mummies with a multidisciplinary team from the German Mummy Project, the Dresden State Art Collections, the Institute for Mummy Studies at Eurac Research in Bolzano, Italy, and also the American-Egyptian Horus Study Group.

Their work informed a now-live interactive exhibit of the male and feminine mummy in Dresden. The teenager's mummy is on display at the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt.

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.

No comments:

Post a Comment