The natural world holds beauty even at a microscopic scale, and each year, Nikon's Small World photo competition opens our eyes to a whole new realm of diminutive detail.

In its 47th year, the contest continues to celebrate the intricacies of nature and the artistry of careful microscopic investigation.

Whether it be a kaleidoscopic slice of meteorite or the translucent head of a tick, the tessellated eye of a horsefly or the web of cracks across a single grain of rice, this year's winners, honorable mentions, and images of distinction are here to give us a glimpse into the unseen.

The first place prize goes to Jason Kirk from the Baylor College of Medicine, who used a custom-made microscope system to capture 200 individual images of a southern live oak leaf, which he then combined to create a single stunning image.

The result is a color-edited mosaic of the leaf's most essential structures, including deep purple pores, snaking cyan vessels, and white trichomes (fine outgrowths that protect against extreme weather).

"The lighting side of it was complicated," explains Kirk.

"Microscope objectives are small and have a very shallow depth of focus. I couldn't just stick a giant light next to the microscope and have the lighting be directional. It would be like trying to light the head of a pin with a light source that's the size of your head. Nearly impossible."

Trichome (white appendages) and stomata (purple pores) on a southern live oak leaf. (Jason Kirk)

Trichome (white appendages) and stomata (purple pores) on a southern live oak leaf. (Jason Kirk)

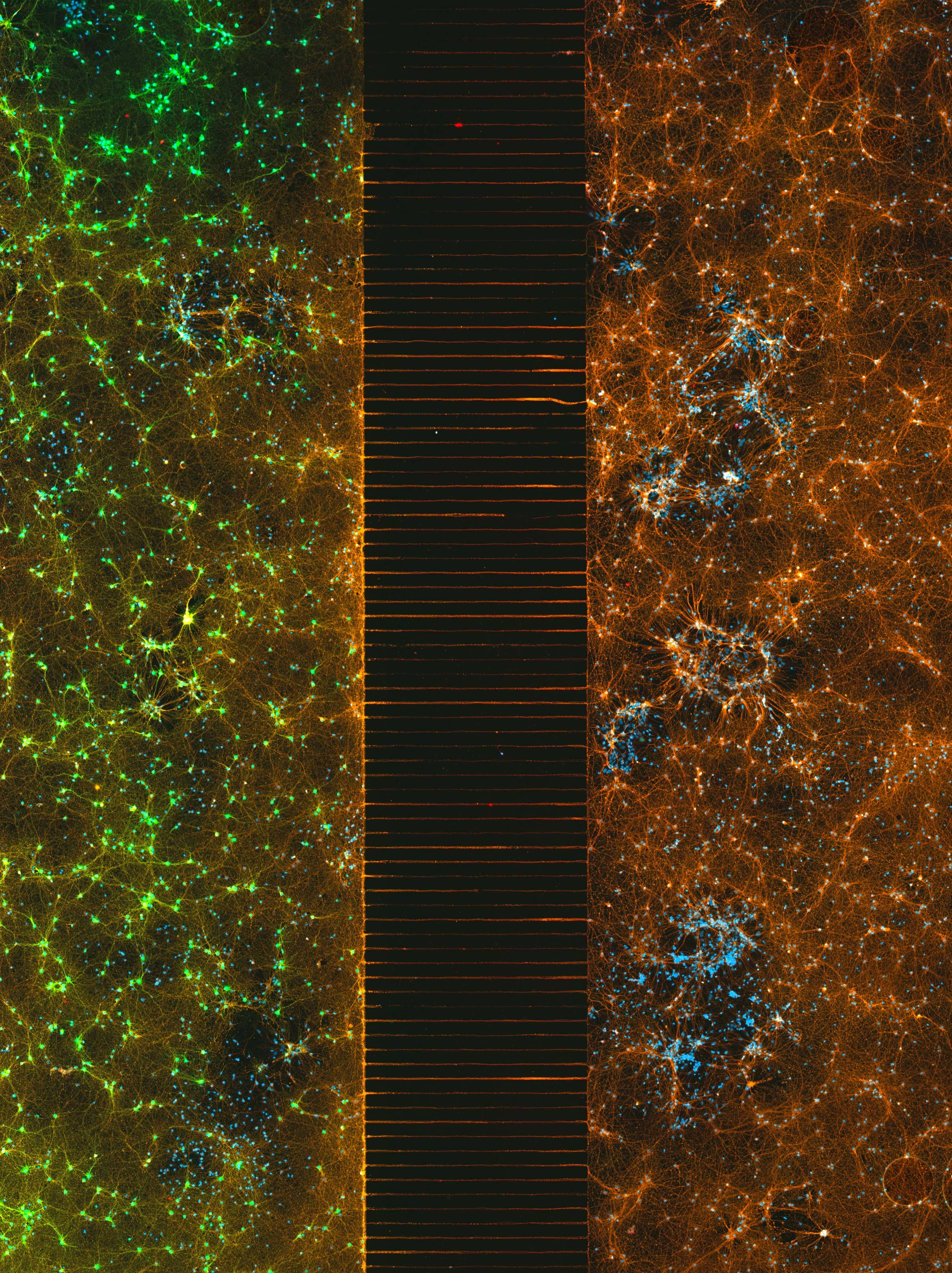

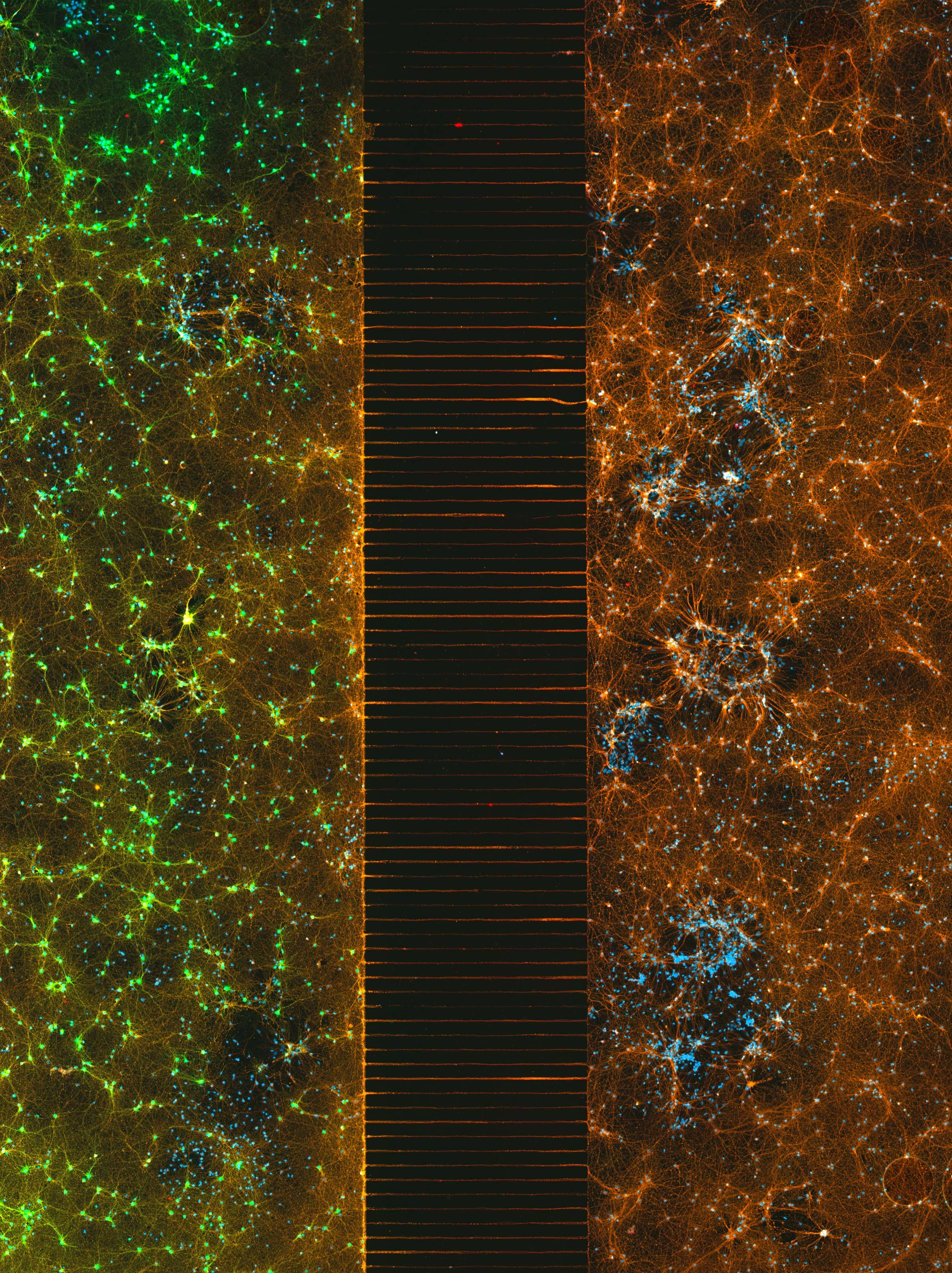

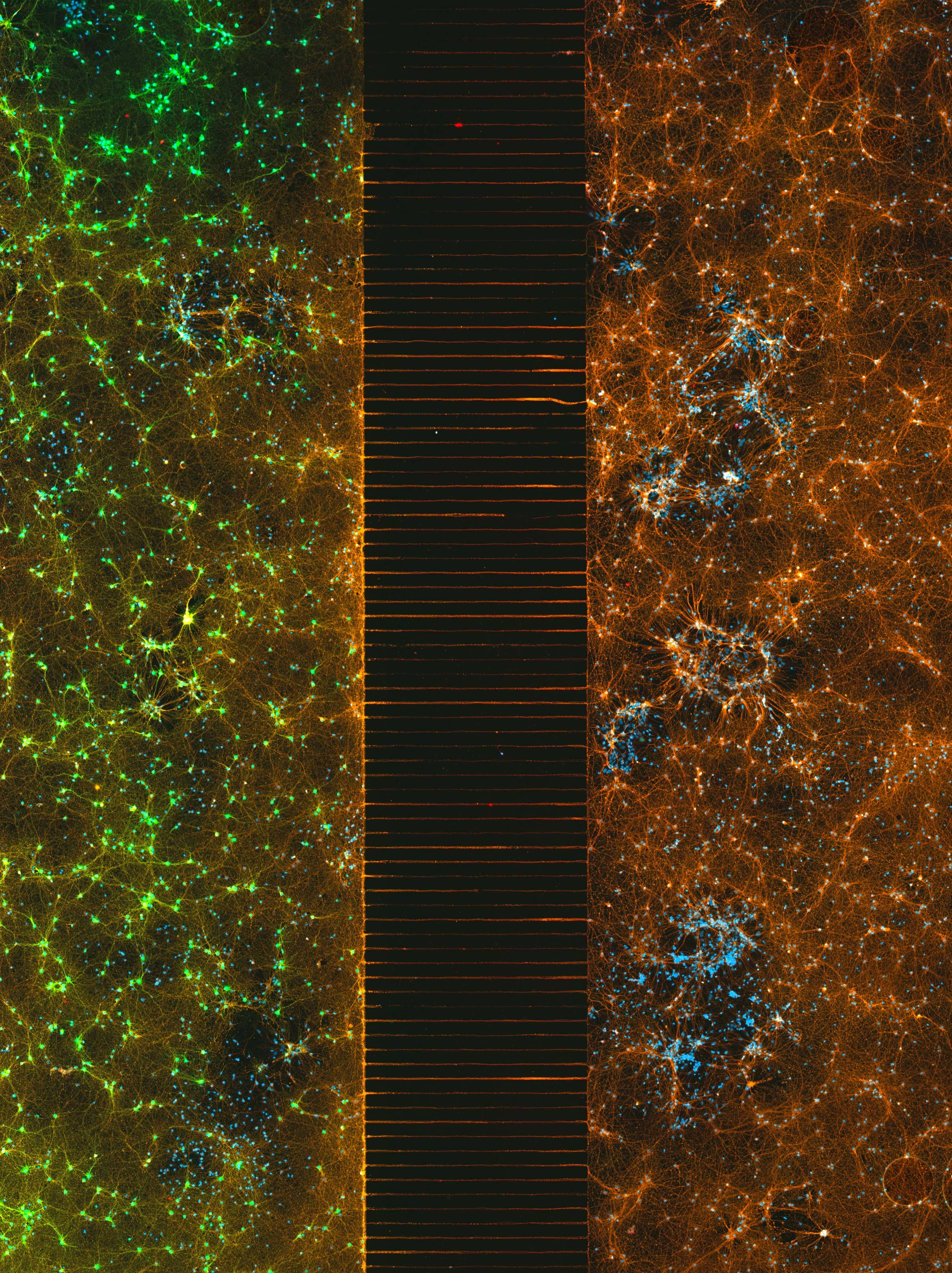

Second place is taken by neuroscientists Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen from Australia, who snapped a constellation of 300,000 networking neurons, split into two populations.

Over time, both networks have grown together via a bridge of axons. Immunostained, the connection creates a gorgeous overall gradient, glowing from orange to green with pockets of blue dotted throughout.

A microfluidic device of neurons in two isolated populations. (Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen)

A microfluidic device of neurons in two isolated populations. (Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen)

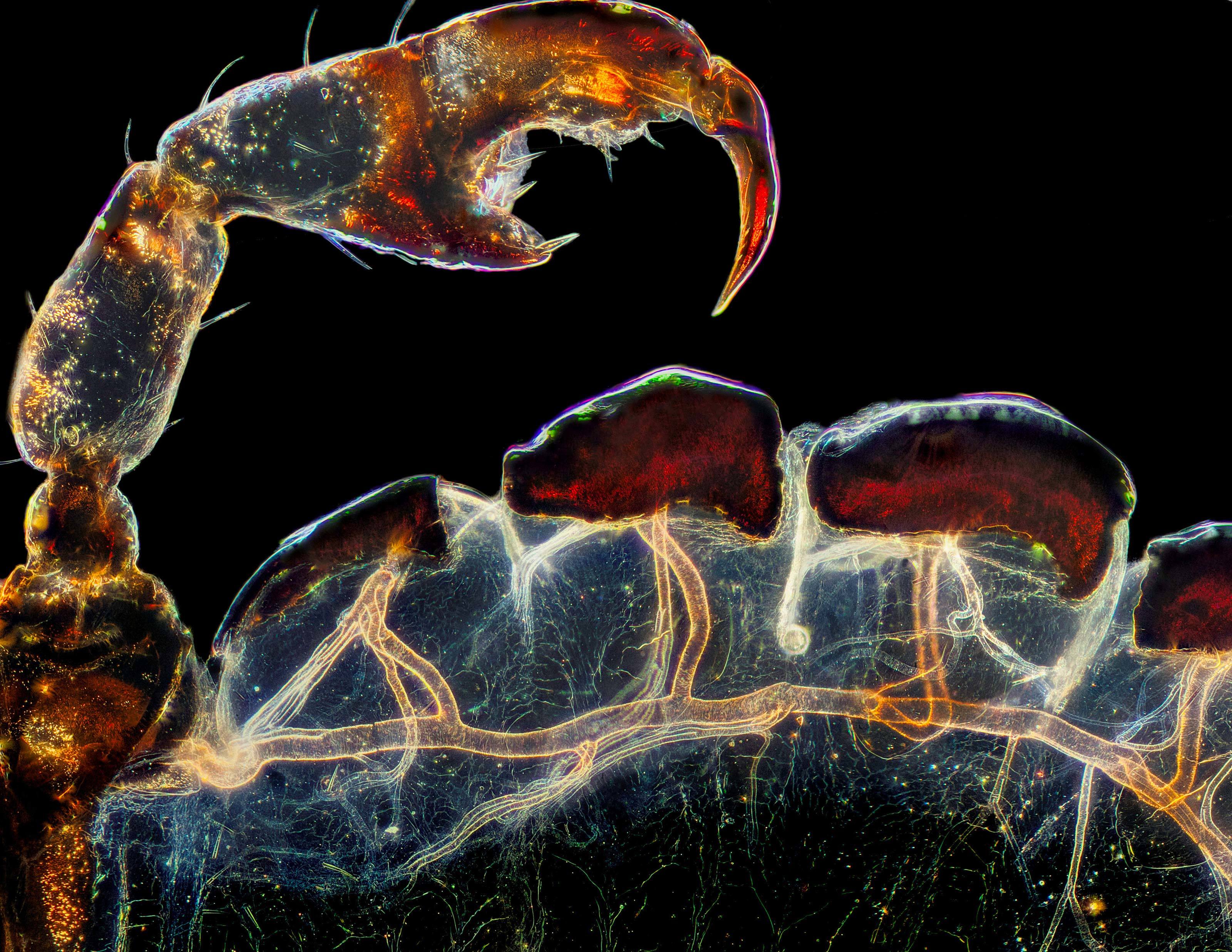

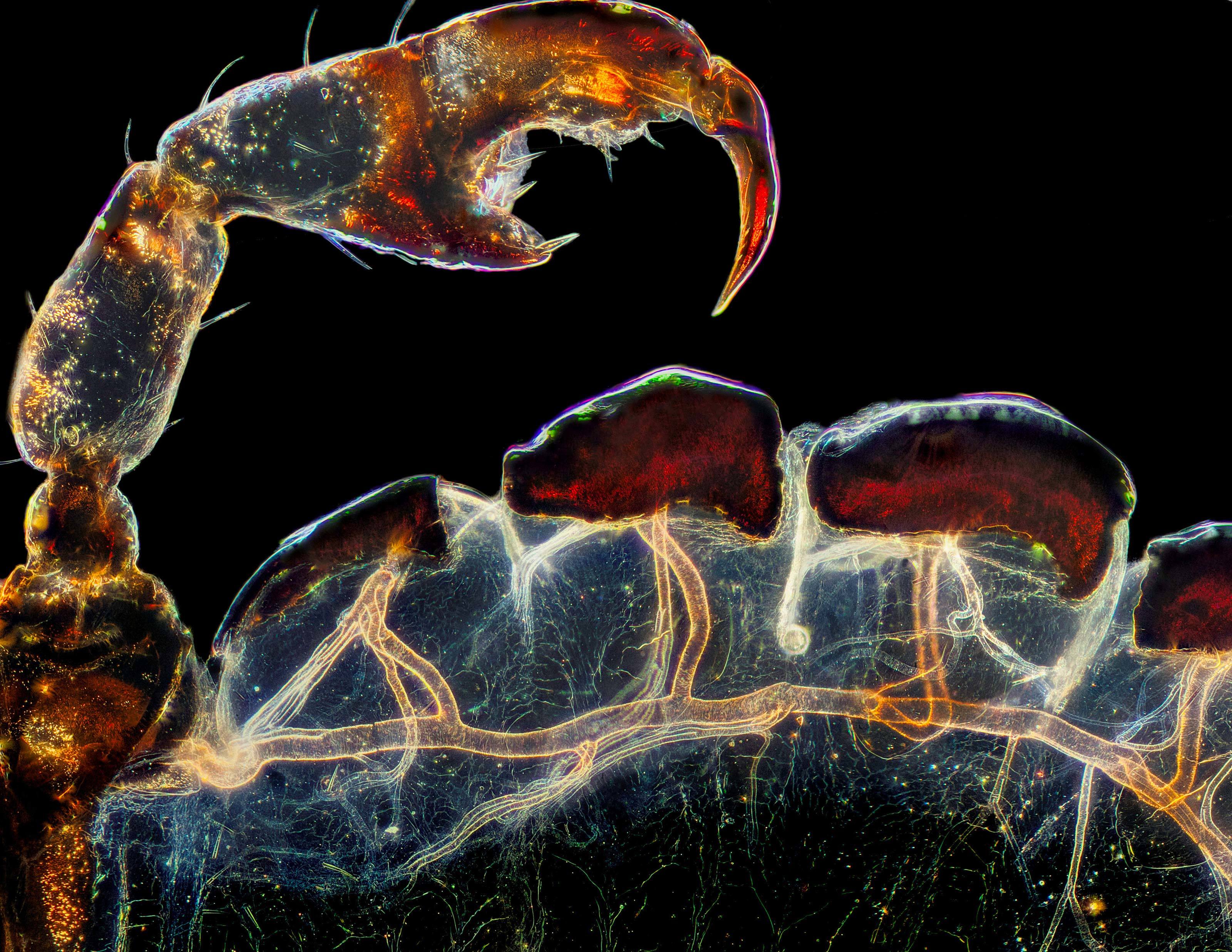

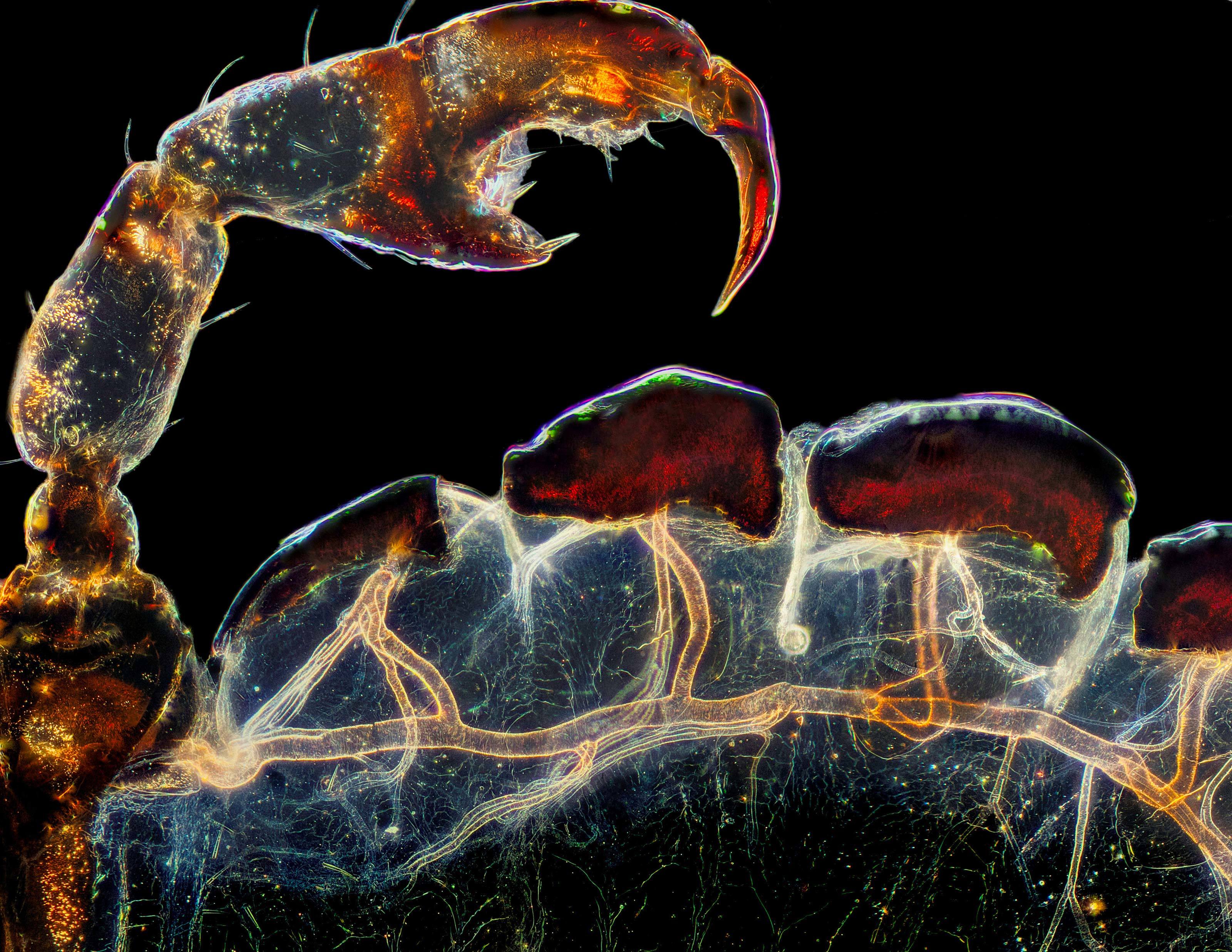

Third place, by Nassau Community College's Frank Reiser, zooms out much further to capture the left side of an individual hog louse, which is a species of lice known as Haematopinus suis among scientists.

The partial body, including a claw and hind leg, are reminiscent of a crab, but of course, these fellas are small enough to crawl on single strands of your hair. Within, a winding pathway of bronchial tubes can be seen, which carry oxygen from limb to limb.

Rear leg, claw, and respiratory trachea of a louse (Haematopinus suis). (Frank Reiser)

Rear leg, claw, and respiratory trachea of a louse (Haematopinus suis). (Frank Reiser)

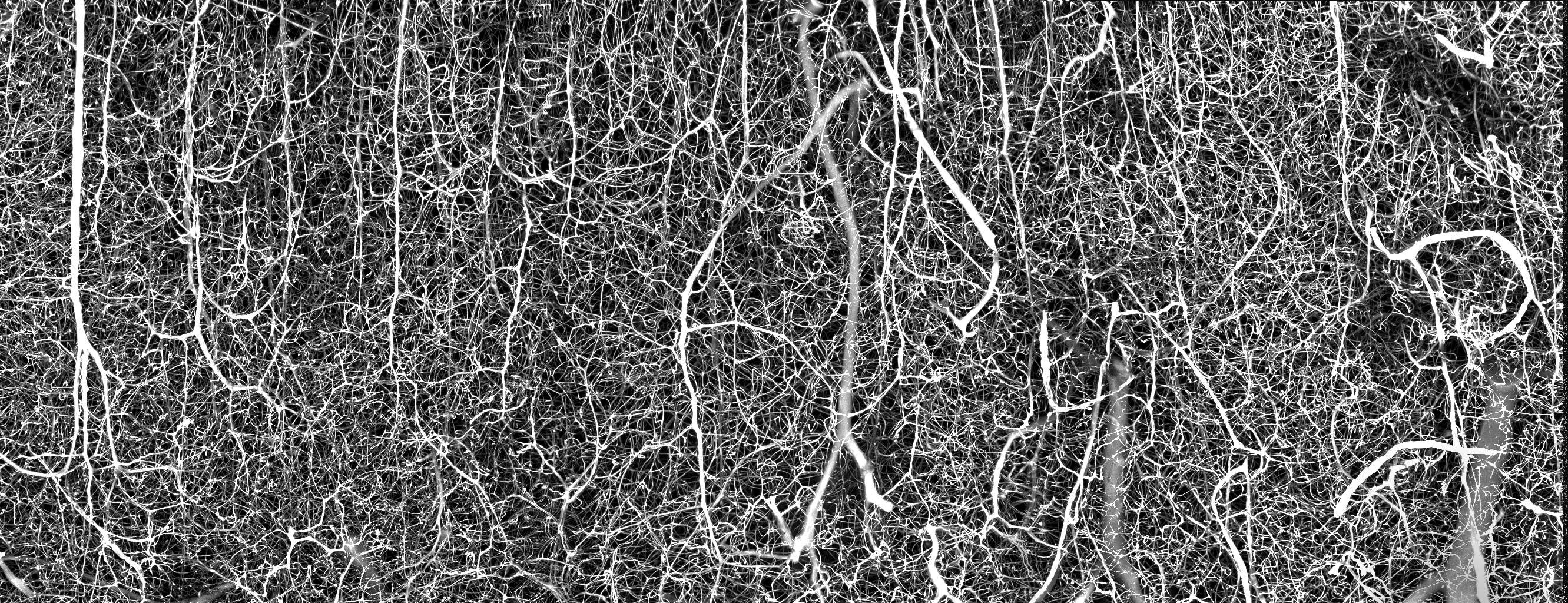

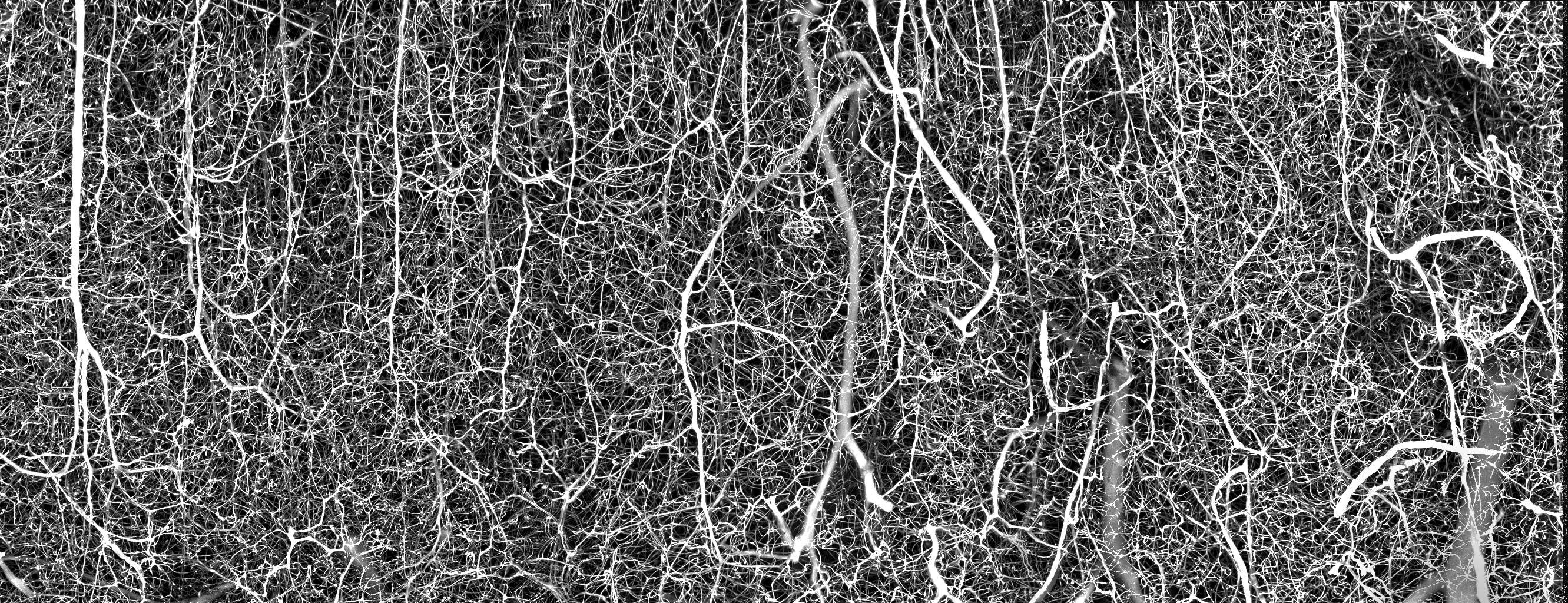

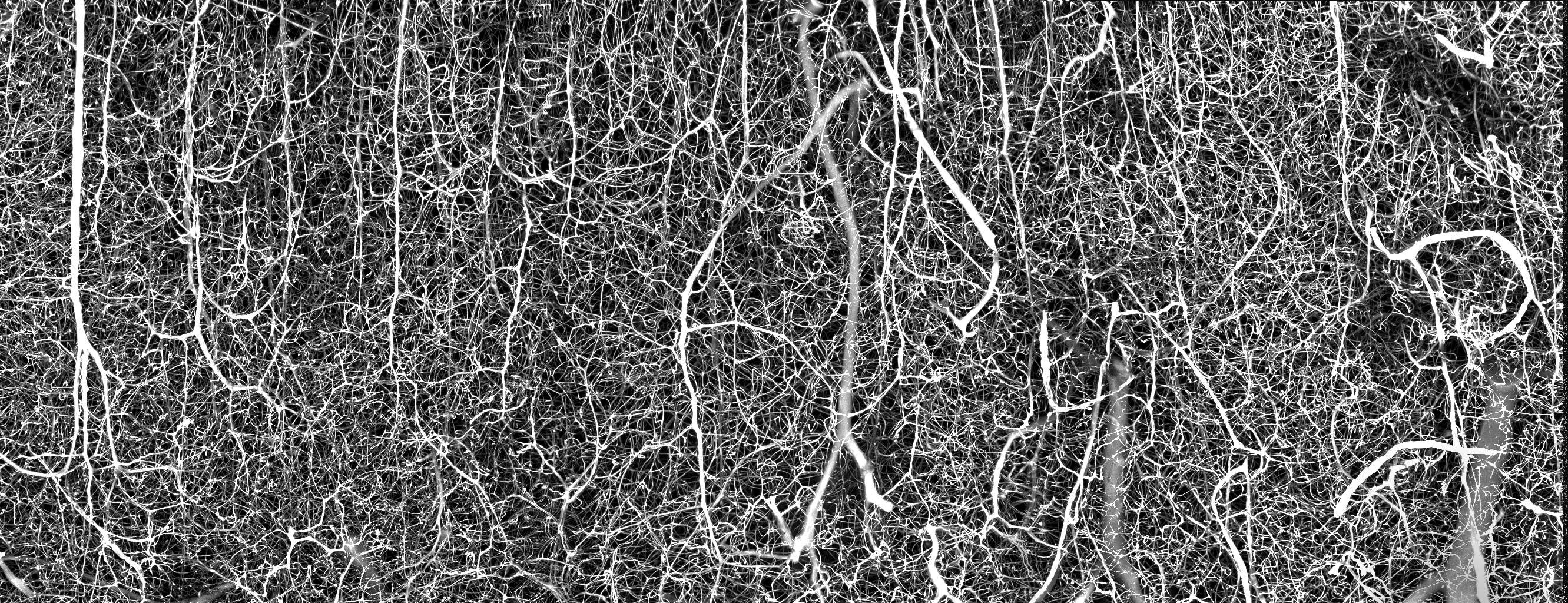

3D vasculature of an adult mouse brain (somatosensory cortex). (Andrea Tedeschi)

Sixth and seventh place were both snapped up by scientists from the same institution – Ohio State University – which is quite the achievement given almost 1,900 images were submitted from all around the world for consideration.

The sixth place winner looks almost like a Pollock painting. The splattering of white lines is a three-dimensional representation of the twisting blood vessels found in an adult mouse brain.

It was submitted by neuroscientist Andrea Tedeschi, who has perfected a technique that allows every single blood vessel in the brain, right down to the finest capillaries, to be imaged.

The exquisite detail is particularly useful for research on strokes, spinal cord injuries, and brain trauma more generally, which can all disrupt the structure and function of blood vessels in the brain.

"We tend to think neurons and neuronal circuits are the most complex structure, but in reality, if you superimpose the images, you can understand that brain vasculature is as complex as the neuron architecture," says Tedeschi.

"If you want to find where a disease is starting, you need access to the structure so you can understand the fine details you might overlook."

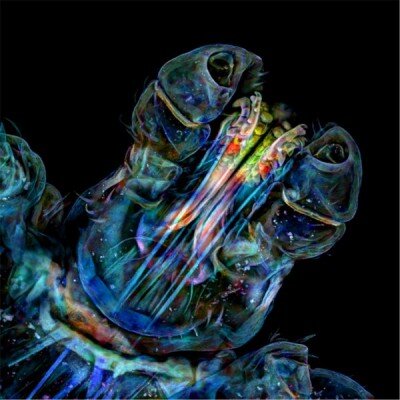

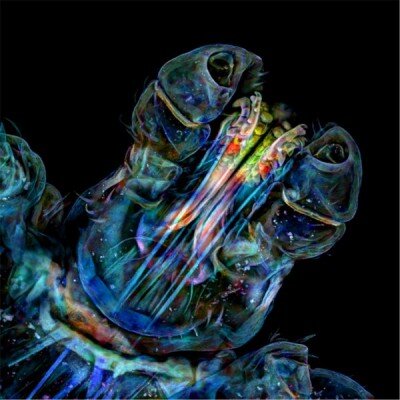

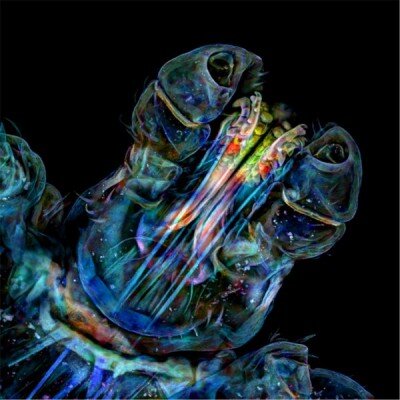

The seventh place winner was captured at the same level of magnification as sixth place, but instead of focusing on the brain of a mouse, Ohio state researchers Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley centered their attention on the head of a tick.

The advanced color scheme they used paints a beautiful picture, which gradually unfolds each and every anatomical layer of the tick's blood-sucking mouth as you trace it with your eyes.

"The image was striking, and the autofluorescence color scheme made the mouth region pop up from the entire image," says Zhang. "You can see fine details in the tick's head, and especially its mouth region, with inverted arrow-like structures. It's a good example of nature's smart designs."

Head of a tick. (Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley)

Head of a tick. (Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley)

The judges this year clearly had their work cut out for them. Some of the honorable mentions and the images of distinction are enough to make your jaw drop.

Take, for instance, this glowing, golden portrait of a 40-million-year-old gnat, trapped in Baltic amber:

40-million-year-old gnat in Baltic amber. (Levon Biss)

40-million-year-old gnat in Baltic amber. (Levon Biss)

Or this extreme close-up of a midge, whose feathery antennae stand out in crisp contrast to the black background.

Midge (Chironomidae diptera). (Erick Francisco Mesén)

Midge (Chironomidae diptera). (Erick Francisco Mesén)

Some of the images submitted were the fruits of hard scientific labor. Others came from professional photographers or amateur microscope enthusiasts with a love for tiny, beautiful things.

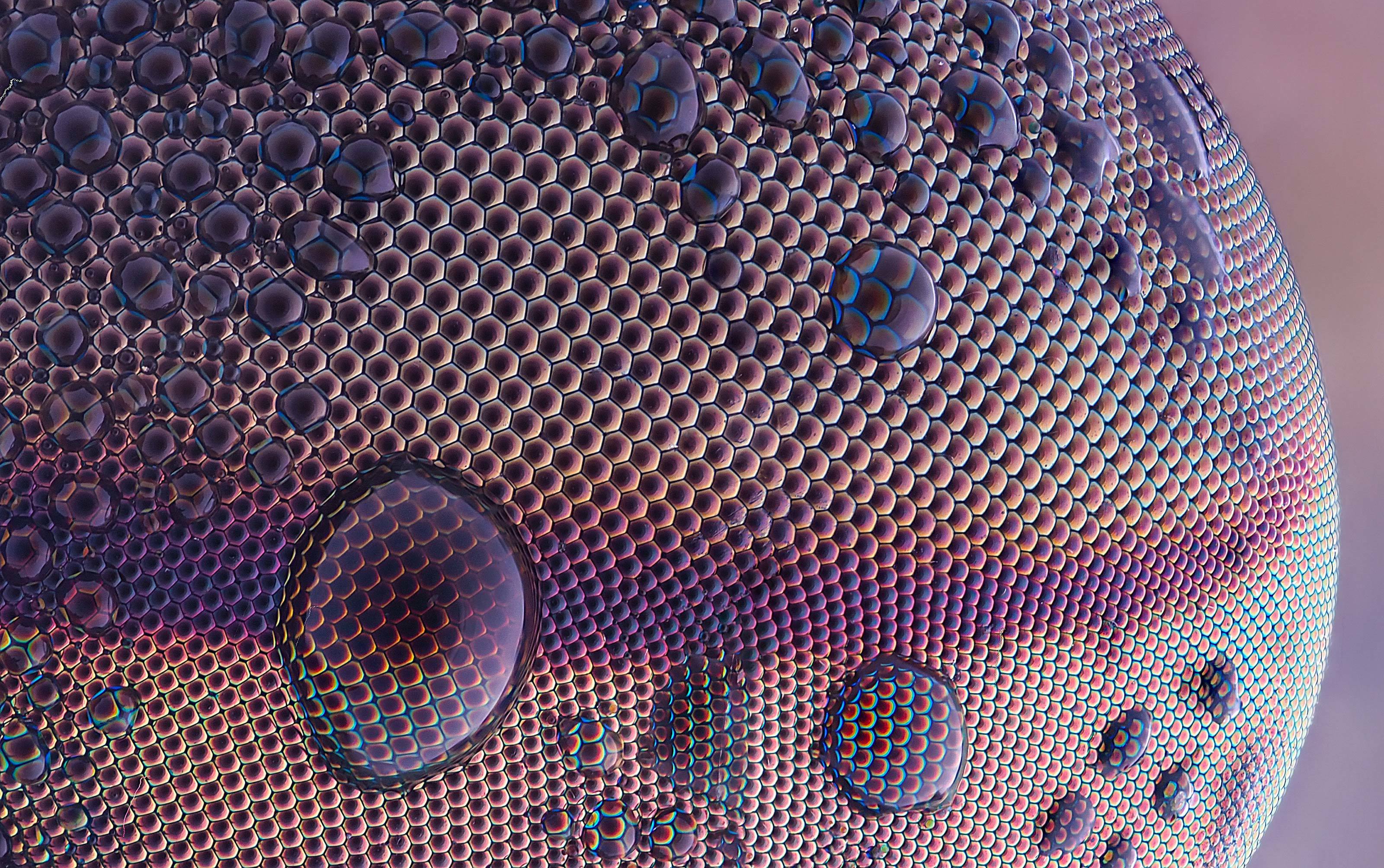

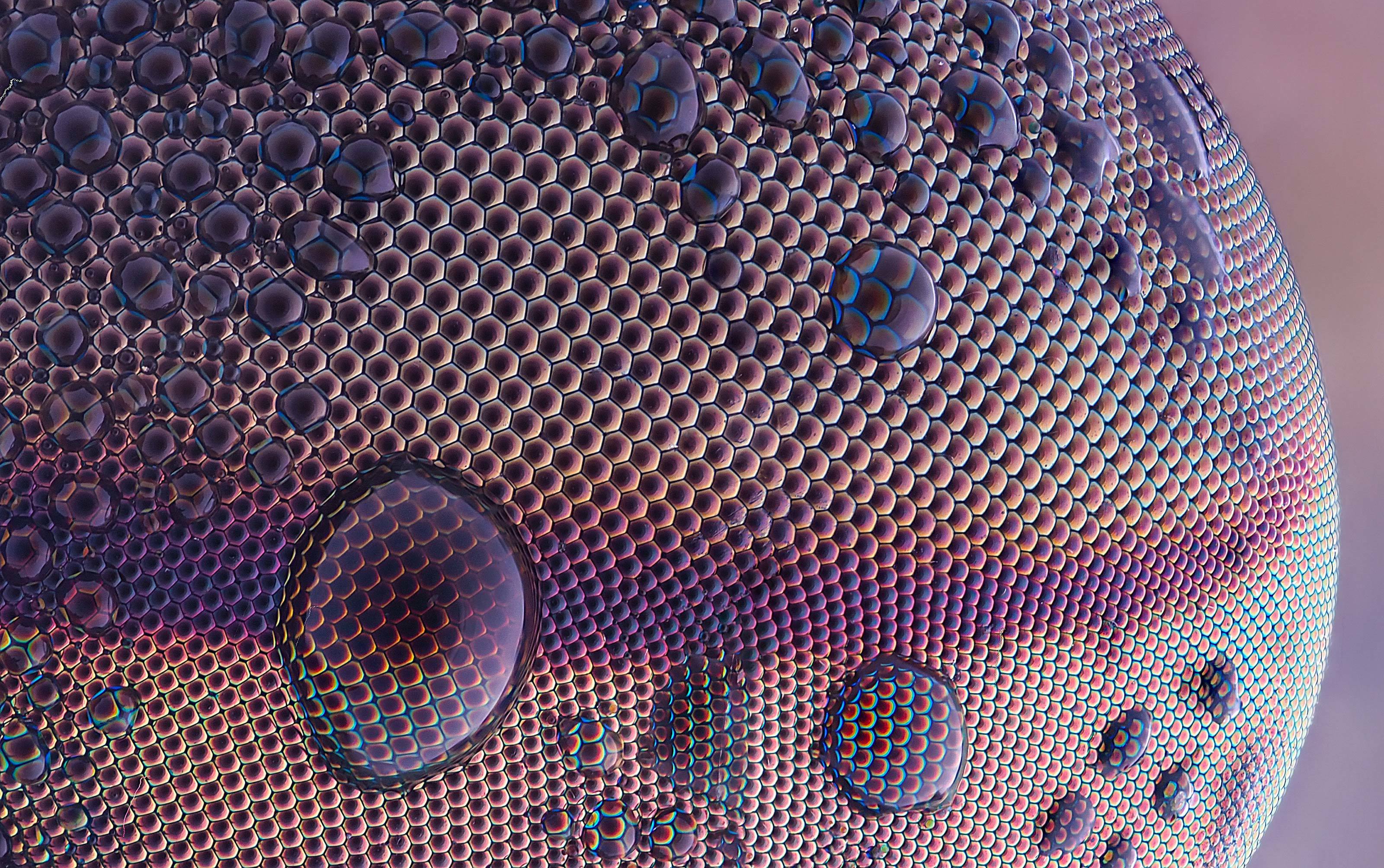

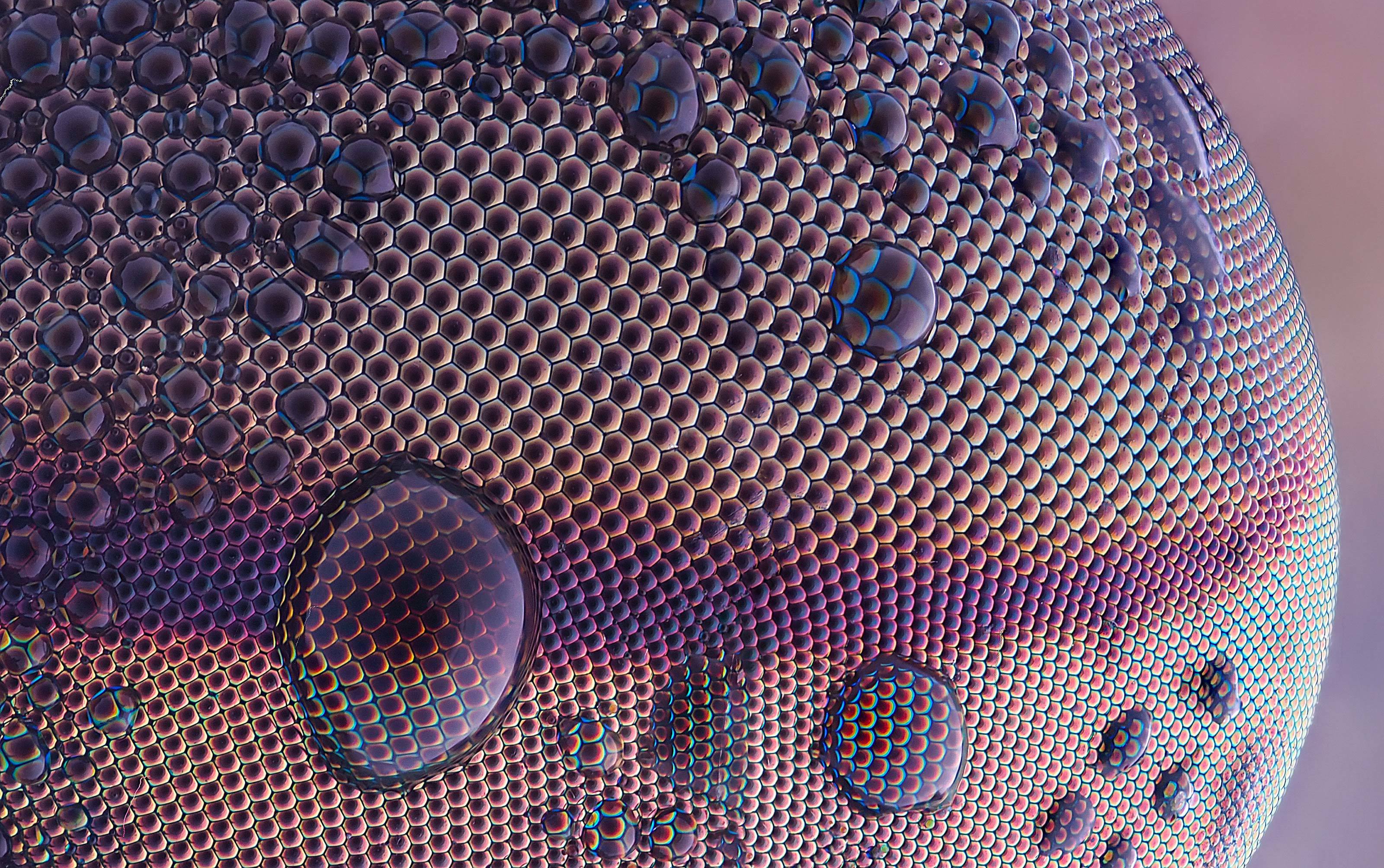

One of the most mesmerizing honorable mentions was taken by photographer Oliver Dum, who likes to focus on the microscopic world.

His award-winning close-up in this case belongs to the compound eye of a horsefly. At such close proximity, each light-sensitive hexagon can be made out, and each combines to create an unbelievably perfect pattern, blown up at times by what look like droplets of water.

Eye of a horsefly. (Tabanus sudeticus). (Oliver Dum)

Eye of a horsefly. (Tabanus sudeticus). (Oliver Dum)

Other images that were submitted answered questions we never even thought we had. Like: Is a single grain of rice really as smooth as it looks to us?

Cracks in a grain of rice. (Roni Hendrawan)

Cracks in a grain of rice. (Roni Hendrawan)

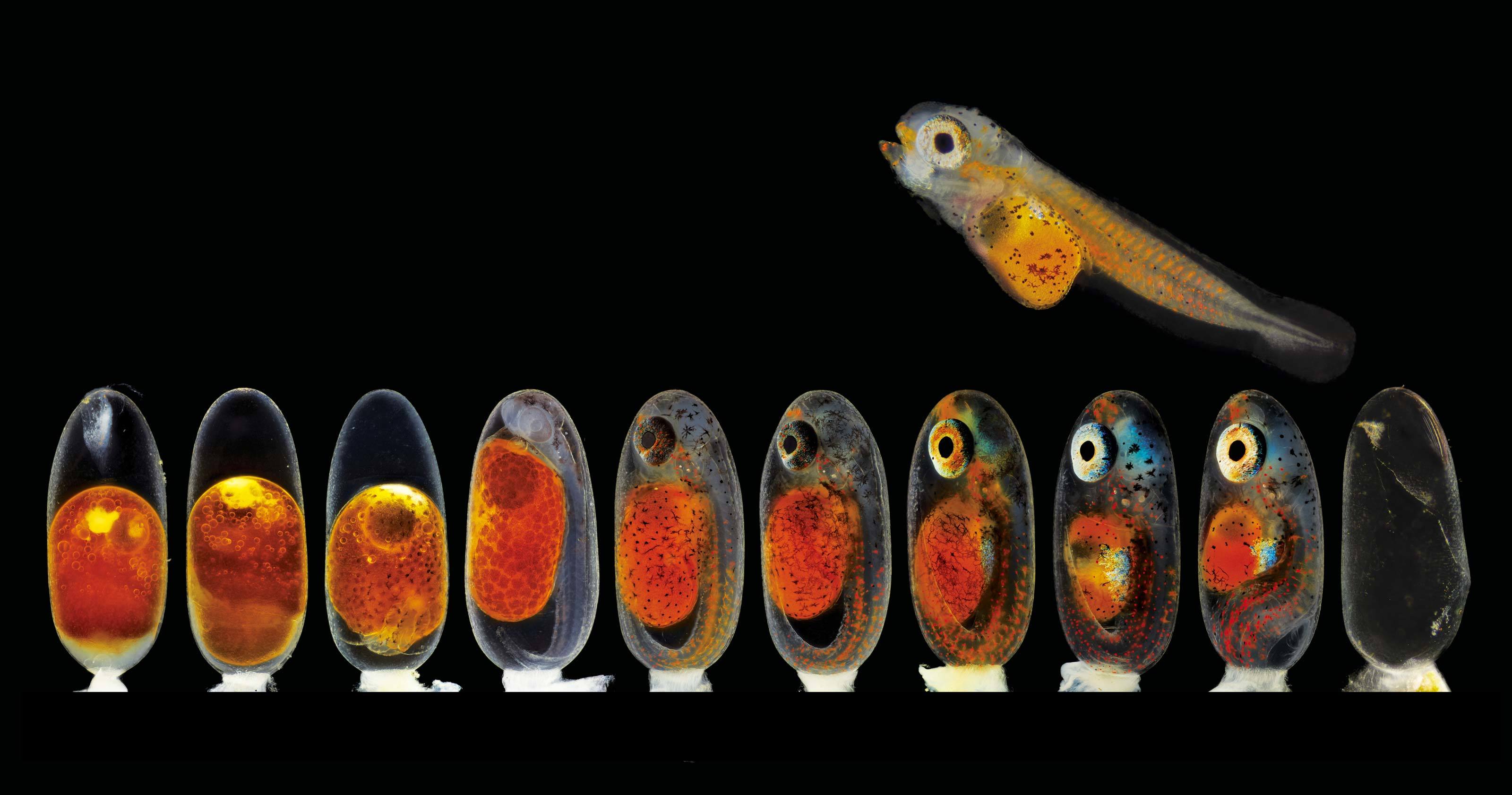

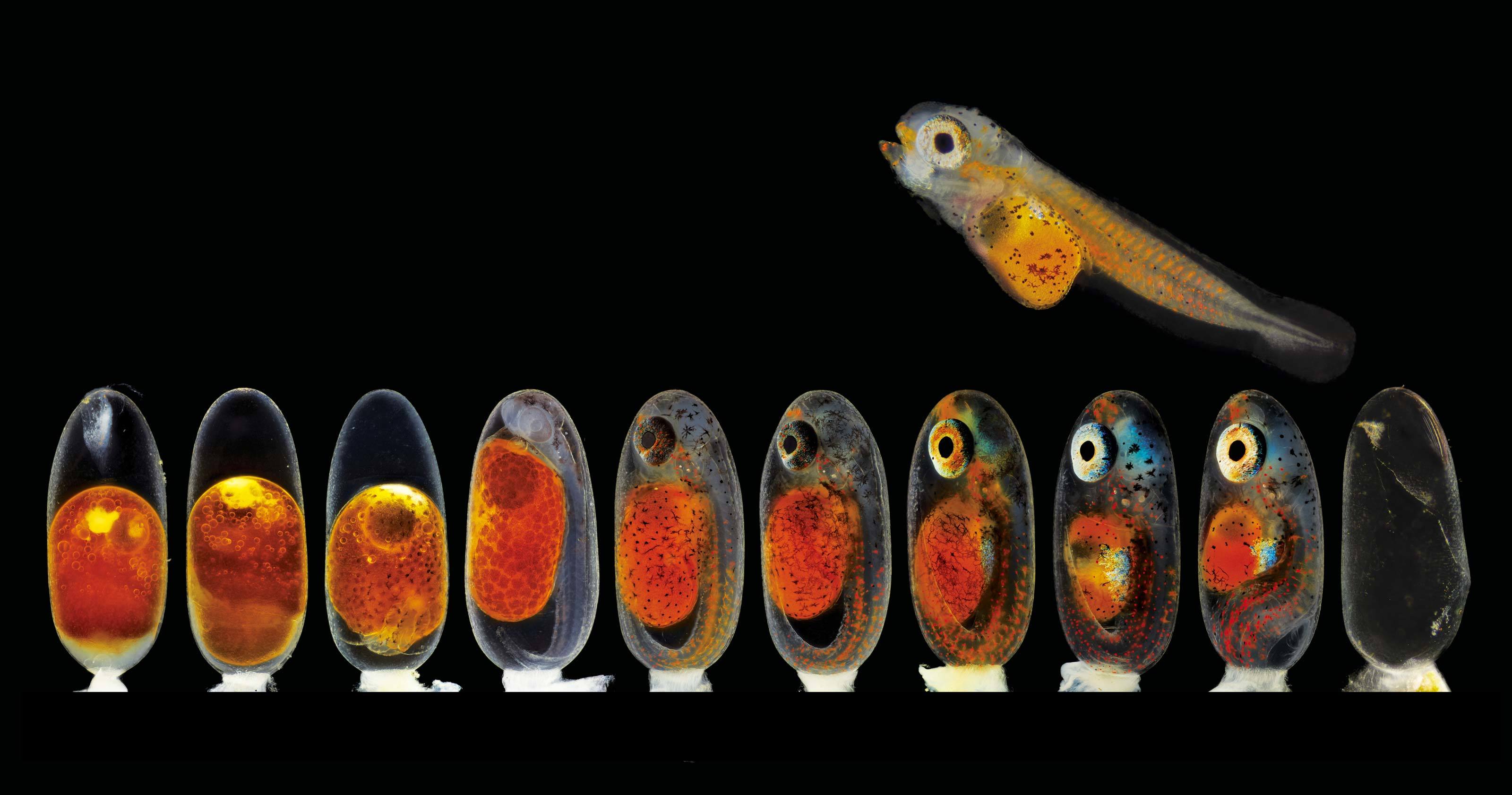

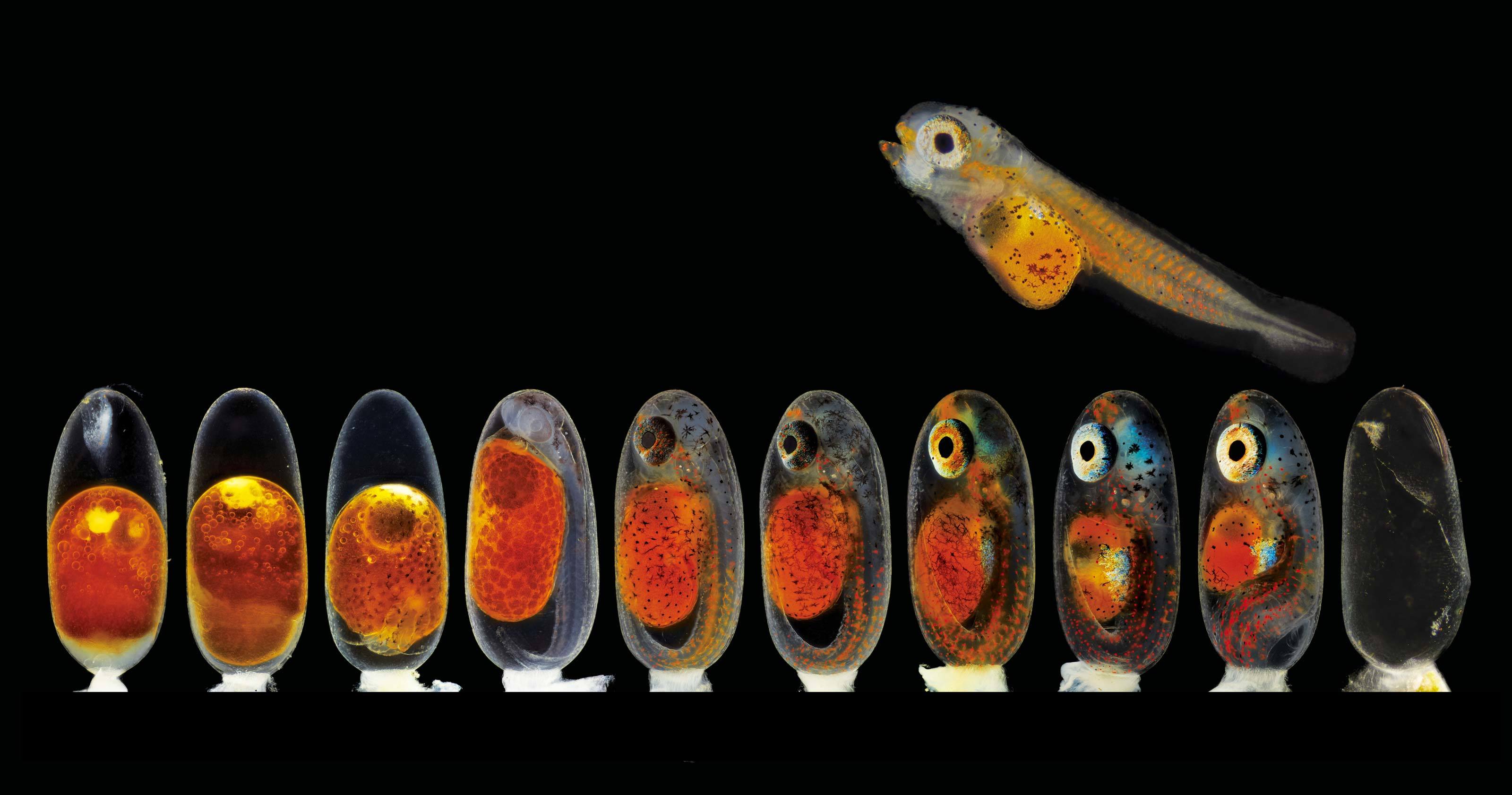

Or: What did Nemo look like as an embryo?

Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) embryos in several developmental stages. (Daniel Knop)

Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) embryos in several developmental stages. (Daniel Knop)

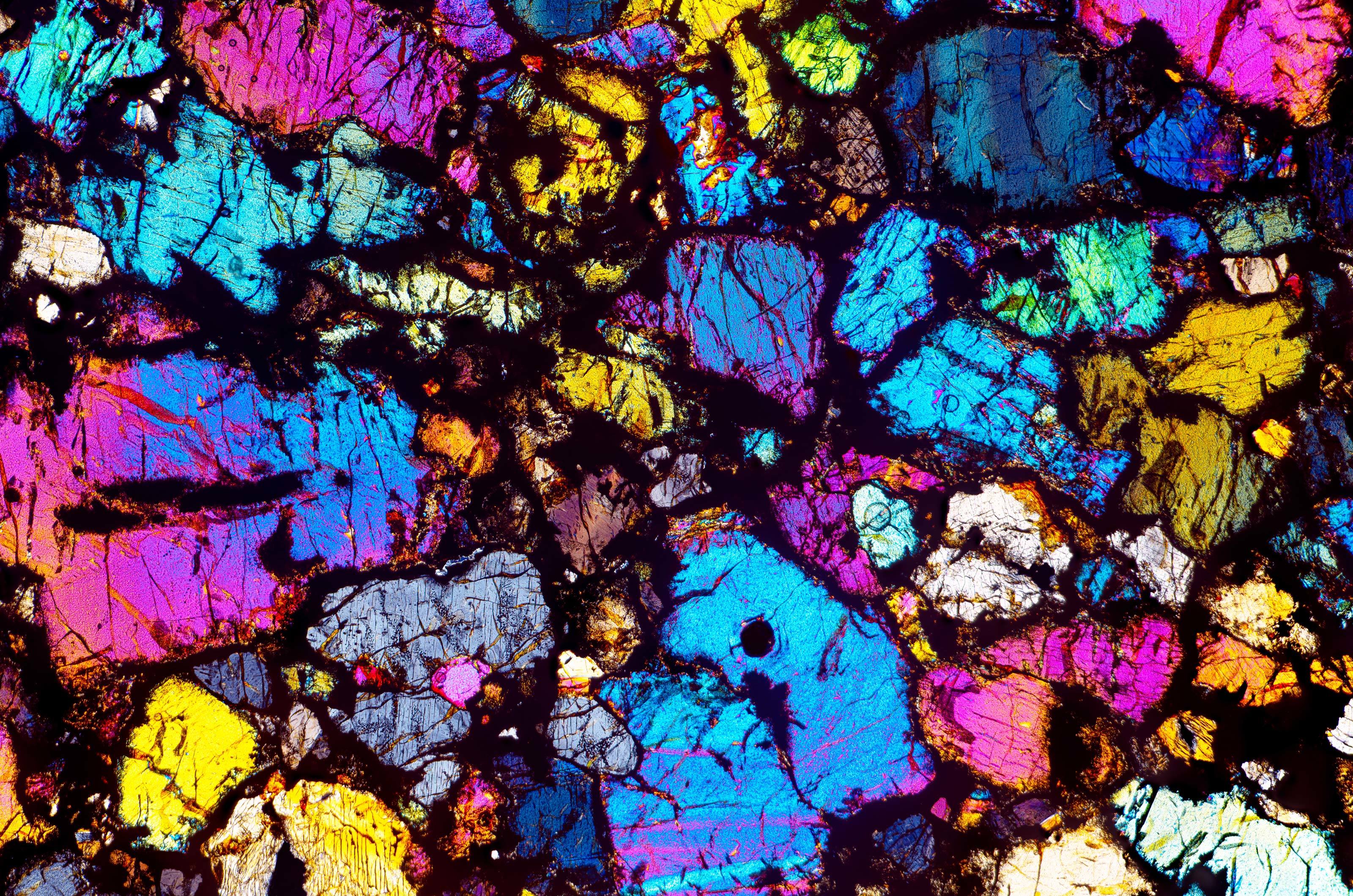

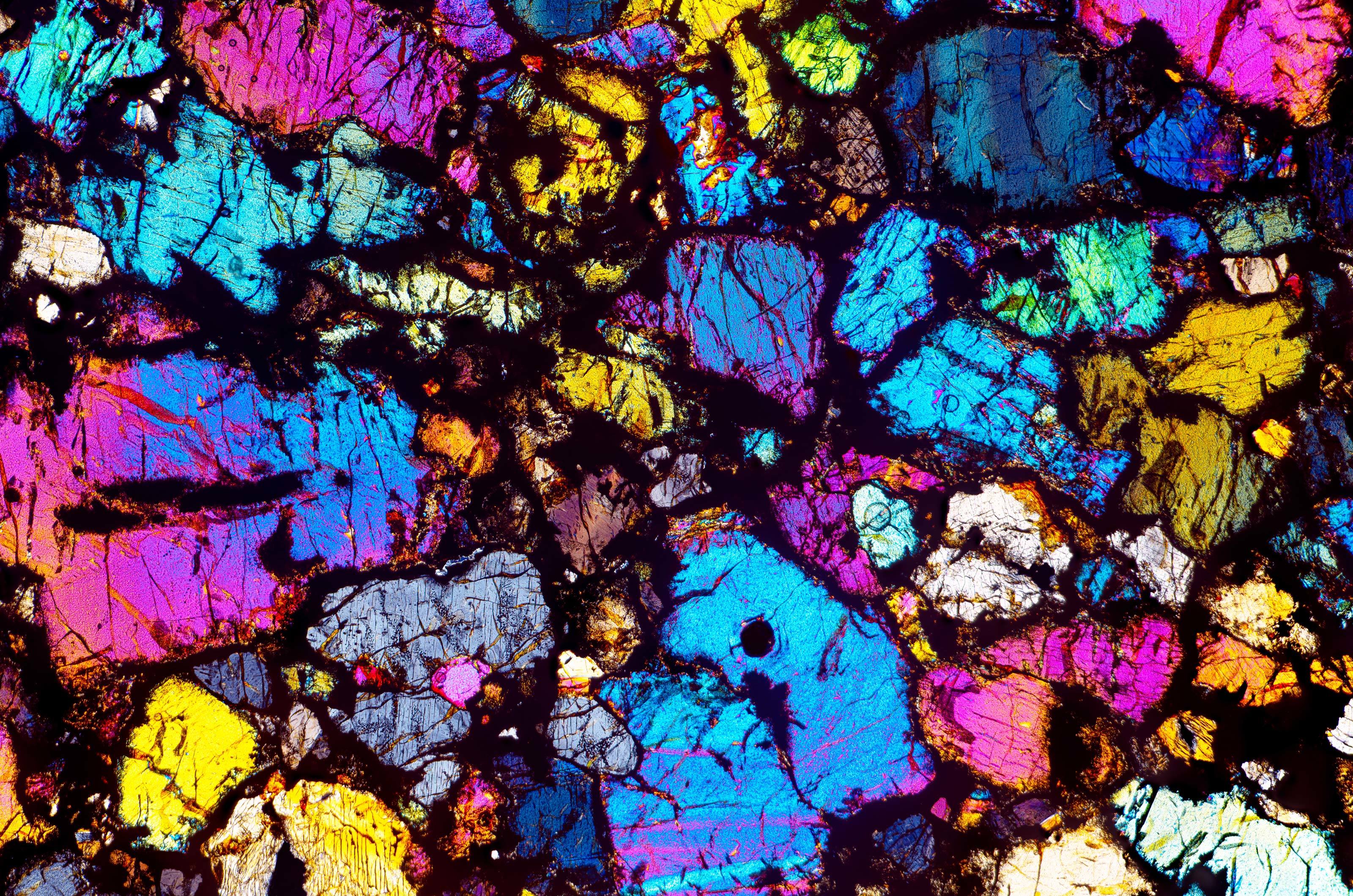

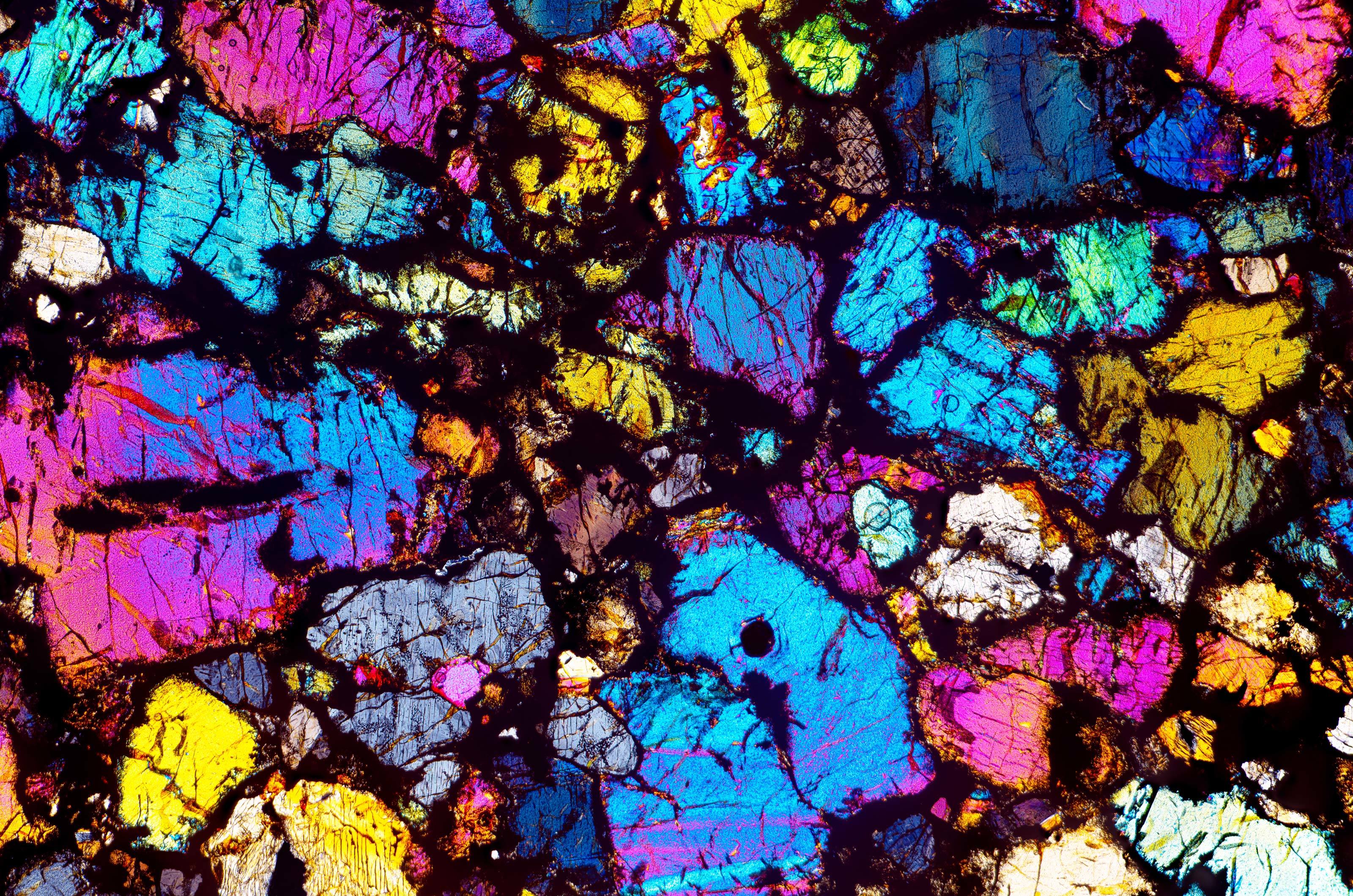

Not all the photos considered were of earthly subjects, either. One out-of-this-world image shows a stained-glass slice of meteorite under the microscope.

Thin slice of a meteorite. (Don Komarechka)

Thin slice of a meteorite. (Don Komarechka)

Perhaps the most grounding image shared by the Nikon judges depicts a single grain of pollen, balanced on a petal, at risk of being blown away.

Pollen grain on a crocus flower petal. (Charles B. Krebs)

Pollen grain on a crocus flower petal. (Charles B. Krebs)

Just as star-gazing can keep our perspective on a universe much larger than ourselves, looking at images of the microscopic world like this one can remind us of the hidden foundation on which we all ultimately float.

The winners of the competition can be found

The natural world holds beauty even at a microscopic scale, and each year, Nikon's Small World photo competition opens our eyes to a whole new realm of diminutive detail.

In its 47th year, the contest continues to celebrate the intricacies of nature and the artistry of careful microscopic investigation.

Whether it be a kaleidoscopic slice of meteorite or the translucent head of a tick, the tessellated eye of a horsefly or the web of cracks across a single grain of rice, this year's winners, honorable mentions, and images of distinction are here to give us a glimpse into the unseen.

The first place prize goes to Jason Kirk from the Baylor College of Medicine, who used a custom-made microscope system to capture 200 individual images of a southern live oak leaf, which he then combined to create a single stunning image.

The result is a color-edited mosaic of the leaf's most essential structures, including deep purple pores, snaking cyan vessels, and white trichomes (fine outgrowths that protect against extreme weather).

"The lighting side of it was complicated," explains Kirk.

"Microscope objectives are small and have a very shallow depth of focus. I couldn't just stick a giant light next to the microscope and have the lighting be directional. It would be like trying to light the head of a pin with a light source that's the size of your head. Nearly impossible."

Trichome (white appendages) and stomata (purple pores) on a southern live oak leaf. (Jason Kirk)

Trichome (white appendages) and stomata (purple pores) on a southern live oak leaf. (Jason Kirk)

Second place is taken by neuroscientists Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen from Australia, who snapped a constellation of 300,000 networking neurons, split into two populations.

Over time, both networks have grown together via a bridge of axons. Immunostained, the connection creates a gorgeous overall gradient, glowing from orange to green with pockets of blue dotted throughout.

A microfluidic device of neurons in two isolated populations. (Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen)

A microfluidic device of neurons in two isolated populations. (Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen)

Third place, by Nassau Community College's Frank Reiser, zooms out much further to capture the left side of an individual hog louse, which is a species of lice known as Haematopinus suis among scientists.

The partial body, including a claw and hind leg, are reminiscent of a crab, but of course, these fellas are small enough to crawl on single strands of your hair. Within, a winding pathway of bronchial tubes can be seen, which carry oxygen from limb to limb.

Rear leg, claw, and respiratory trachea of a louse (Haematopinus suis). (Frank Reiser)

Rear leg, claw, and respiratory trachea of a louse (Haematopinus suis). (Frank Reiser)

3D vasculature of an adult mouse brain (somatosensory cortex). (Andrea Tedeschi)

Sixth and seventh place were both snapped up by scientists from the same institution – Ohio State University – which is quite the achievement given almost 1,900 images were submitted from all around the world for consideration.

The sixth place winner looks almost like a Pollock painting. The splattering of white lines is a three-dimensional representation of the twisting blood vessels found in an adult mouse brain.

It was submitted by neuroscientist Andrea Tedeschi, who has perfected a technique that allows every single blood vessel in the brain, right down to the finest capillaries, to be imaged.

The exquisite detail is particularly useful for research on strokes, spinal cord injuries, and brain trauma more generally, which can all disrupt the structure and function of blood vessels in the brain.

"We tend to think neurons and neuronal circuits are the most complex structure, but in reality, if you superimpose the images, you can understand that brain vasculature is as complex as the neuron architecture," says Tedeschi.

"If you want to find where a disease is starting, you need access to the structure so you can understand the fine details you might overlook."

The seventh place winner was captured at the same level of magnification as sixth place, but instead of focusing on the brain of a mouse, Ohio state researchers Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley centered their attention on the head of a tick.

The advanced color scheme they used paints a beautiful picture, which gradually unfolds each and every anatomical layer of the tick's blood-sucking mouth as you trace it with your eyes.

"The image was striking, and the autofluorescence color scheme made the mouth region pop up from the entire image," says Zhang. "You can see fine details in the tick's head, and especially its mouth region, with inverted arrow-like structures. It's a good example of nature's smart designs."

Head of a tick. (Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley)

Head of a tick. (Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley)

The judges this year clearly had their work cut out for them. Some of the honorable mentions and the images of distinction are enough to make your jaw drop.

Take, for instance, this glowing, golden portrait of a 40-million-year-old gnat, trapped in Baltic amber:

40-million-year-old gnat in Baltic amber. (Levon Biss)

40-million-year-old gnat in Baltic amber. (Levon Biss)

Or this extreme close-up of a midge, whose feathery antennae stand out in crisp contrast to the black background.

Midge (Chironomidae diptera). (Erick Francisco Mesén)

Midge (Chironomidae diptera). (Erick Francisco Mesén)

Some of the images submitted were the fruits of hard scientific labor. Others came from professional photographers or amateur microscope enthusiasts with a love for tiny, beautiful things.

One of the most mesmerizing honorable mentions was taken by photographer Oliver Dum, who likes to focus on the microscopic world.

His award-winning close-up in this case belongs to the compound eye of a horsefly. At such close proximity, each light-sensitive hexagon can be made out, and each combines to create an unbelievably perfect pattern, blown up at times by what look like droplets of water.

Eye of a horsefly. (Tabanus sudeticus). (Oliver Dum)

Eye of a horsefly. (Tabanus sudeticus). (Oliver Dum)

Other images that were submitted answered questions we never even thought we had. Like: Is a single grain of rice really as smooth as it looks to us?

Cracks in a grain of rice. (Roni Hendrawan)

Cracks in a grain of rice. (Roni Hendrawan)

Or: What did Nemo look like as an embryo?

Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) embryos in several developmental stages. (Daniel Knop)

Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) embryos in several developmental stages. (Daniel Knop)

Not all the photos considered were of earthly subjects, either. One out-of-this-world image shows a stained-glass slice of meteorite under the microscope.

Thin slice of a meteorite. (Don Komarechka)

Thin slice of a meteorite. (Don Komarechka)

Perhaps the most grounding image shared by the Nikon judges depicts a single grain of pollen, balanced on a petal, at risk of being blown away.

Pollen grain on a crocus flower petal. (Charles B. Krebs)

Pollen grain on a crocus flower petal. (Charles B. Krebs)

Just as star-gazing can keep our perspective on a universe much larger than ourselves, looking at images of the microscopic world like this one can remind us of the hidden foundation on which we all ultimately float.

The winners of the competition can be found

Trichome (white appendages) and stomata (purple pores) on a southern live oak leaf. (Jason Kirk)

Trichome (white appendages) and stomata (purple pores) on a southern live oak leaf. (Jason Kirk) A microfluidic device of neurons in two isolated populations. (Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen)

A microfluidic device of neurons in two isolated populations. (Esmeralda Paric and Holly Stefen) Rear leg, claw, and respiratory trachea of a louse (Haematopinus suis). (Frank Reiser)

Rear leg, claw, and respiratory trachea of a louse (Haematopinus suis). (Frank Reiser)

Head of a tick. (Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley)

Head of a tick. (Tong Zhang and Paul Stoodley) 40-million-year-old gnat in Baltic amber. (Levon Biss)

40-million-year-old gnat in Baltic amber. (Levon Biss) Midge (Chironomidae diptera). (Erick Francisco Mesén)

Midge (Chironomidae diptera). (Erick Francisco Mesén) Eye of a horsefly. (Tabanus sudeticus). (Oliver Dum)

Eye of a horsefly. (Tabanus sudeticus). (Oliver Dum) Cracks in a grain of rice. (Roni Hendrawan)

Cracks in a grain of rice. (Roni Hendrawan) Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) embryos in several developmental stages. (Daniel Knop)

Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) embryos in several developmental stages. (Daniel Knop) Thin slice of a meteorite. (Don Komarechka)

Thin slice of a meteorite. (Don Komarechka) Pollen grain on a crocus flower petal. (Charles B. Krebs)

Pollen grain on a crocus flower petal. (Charles B. Krebs)

No comments:

Post a Comment