While the globe struggles to finish the COVID-19 pandemic, experts say we're already handling another global infectious-disease threat.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria aren't getting the maximum amount attention as COVID-19, since the diseases they cause spread slowly and steadily, instead of taking the globe by storm in an exceedingly short period of your time.

But bacteria could become a COVID-19-level threat, experts say. And it'll happen in an exceedingly slow march.

According to the CDC, nearly 3 million Americans per annum contract an antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection. Of those, roughly 35,000 die.

Globally, approximately 700,000 die from these infections per annum. the planet Health Organisation projects that, at current rates, around 10 million people could die from antibiotic-resistant infections annually by 2050.

Because of the overprescription of antibiotics, the overuse of them in livestock, and other factors, many alternative varieties of bacterial infections including strains of gonorrhea, tuberculosis, and salmonella became extremely hard, sometimes even impossible, to treat. That's because the little portion of bacteria that survive these antibiotics evolve and reproduce, developing resistance. round the world, 230,000 die every year from antibiotic-resistant tuberculosis alone.

"It's increasingly likely that that bacterial infection are very difficult to treat if not untreatable, and untreatable bacterial infections are bad. Untreatable bacterial infections do plenty of harm," Sarah Fortune, a professor of immunology and infectious diseases at university, told Insider. "They kill people."

Steffanie Strathdee, a professor of medication at the University of California, San Diego, told Insider that we're not talking about the threat nearly enough.

"Unlike COVID-19, which came along suddenly and burst on the scene, the superbug crisis has been simmering along," Strahdee said. "It's already an epidemic. It's already a world crisis, and it's getting worse under COVID."

Tom Frieden, the previous CDC director and also the CEO of Resolve to avoid wasting Lives, told Insider that the US Government needs a more aggressive and multifaceted approach to fight what he calls "nightmare bacteria." He added that the medical profession should focus specifically on how communicable disease spread through hospitals

"I have absolutely little doubt that in 20 or 40 years, we'll recall at healthcare because it was implemented in 2020 and shake our heads in wonder about how they may have let such a large amount of infections spread in healthcare facilities," Frieden said.

"We're just not anywhere near where we'd like to be in terms of infection prevention and control."

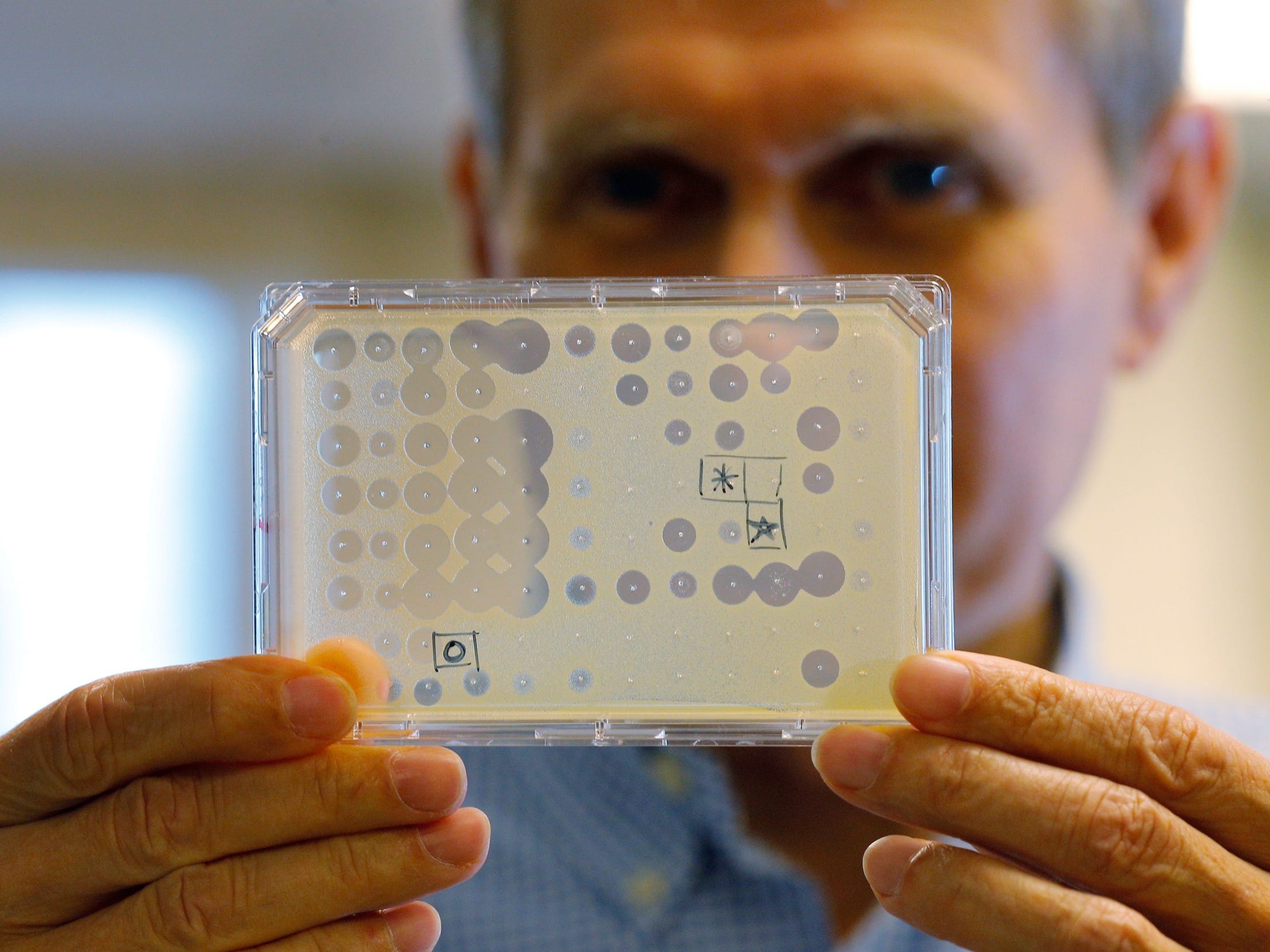

An antibiotic test. (Brian Snyder/Reuters)

An antibiotic test. (Brian Snyder/Reuters)

A 'dysfunctional' public-health system makes the matter hard to repair

Much of the eye and resources that might be dedicated to the bacteria threat are currently directed toward trying to defeat COVID-19, Strathdee said. therein sense, the coronavirus pandemic may, perversely, be making the antibiotic-resistant bacteria problem worse.

In July, the WHO needed more careful use of antibiotics among COVID-19 patients to assist curb the threat of antibiotic resistance. A May review found that among about 2,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients worldwide, 72 percent received antibiotics although only 8 percent had documented bacterial or fungal infections.

As bacteria become more proof against antibiotics, the chance of catastrophic consequences increases. E. coli, as an example, causes scores of urinary-tract infections per annum.

If an especially antibiotic-resistant strain of it develops, it could spread and kill "countless young women," in step with Lance Price, founding director of the Antibiotic Resistance Action Centre at Washington University.

"They could visit the doctor with what they think may be a routine bladder infection and find yourself dead from bloodstream infections because the doctors try to fail to treat their infections because it ascends from the bladder to the kidneys and into the blood," Price said.

The COVID-19 pandemic, Price added, has exposed how our "dysfunctional" public-health system "has left us susceptible to slow-spreading, antibiotic-resistant bacteria."

"The US isn't prepared to cater to bacterial pandemics, as proven by our inability to handle many simultaneous, ongoing epidemics and pandemics of multidrug-resistant bacteria that are currently circulating," Price said.

Fortune told Insider that bacteria will gain resistance to new antibiotics over time, so we'll must watch out about how we use them and keep developing new drugs to face the matter.

But it has been decades since a brand new class of antibiotics has been developed. Companies like Achaogen and Aradigm, which focused on creating new ones, have shuttered over the past few years. And pharmaceutical giants like Novartis and Allergan have abandoned the hassle altogether.

Drug manufacturers, Fortune said, don't see the maximum amount profit in developing new antibiotics as they are doing other drugs. Many have invested in developing a replacement antibiotic and failed, she said, and that they can make extra money by developing drugs people take regularly instead of only they need an infection.

Companies also can't charge the maximum amount for antibiotics as they will for other drugs they could develop, and therefore the shelf-life of an antibiotic is comparatively short, Fortune said. So if we're visiting get new antibiotics, we'd like to seek out ways to induce companies to prioritise creating them.

The uk is functioning to form such incentives.

The country is investing US$60 million into antibiotic development through an innovation fund, and its National Health Service has developed a subscription-style funding arrangement designed to spur pharmaceutical companies to form new antibiotics. per that plan, the NHS would pay companies up-front for access to antibiotics, instead of paying for them supported what number pills they sell.

Fighting bacteria with more viruses

Outside of developing new antibiotics, a sort of virus may well be the answer.

A category of virus called phages naturally target and kill specific styles of bacteria. If you'll be able to find the actual phage that kills the bacteria an individual is infected with, you'll use it to treat their infection.

Strathdee has personal experience with this type of treatment. Her husband was infected by a superbug in 2015, and when antibiotics weren't working, Strathdee reached resolute people studying phages and superbugs.

By searching through sewage and barnyard waste, where phages are plentiful, and thru the phages they'd already isolated, the researchers found the phage that matched the bacteria in Strathdee's isolate. They injected him with billions of phages in a very phage cocktail, and he made a full recovery.

"Not only am I an infectious-disease epidemiologist, but my very own family's life was turned the wrong way up and has never been the identical as a results of a superbug. And if it caught me off guard, it's visiting catch everybody off guard, because the common person doesn't understand how big of an issue this is often," Strathdee said.

The centre she co-founded, IPATH, is now preparing to start the primary National Institutes of Health-funded clinical test of phage therapy.

"What we want may be a giant phage library that might be open-source, that might be wont to match phages to a particular bacterial infection and used with antibiotics to cure these superbugs," Strathdee said.

Experts also stress that the US must be better tracking the spread of superbugs, developing antibiotics, researching phage therapy, using existing antibiotics more carefully, and investing way more into tackling this problem before it becomes a bigger crisis.

Addressing the difficulty also requires international cooperation, Frieden said.

"The bottom line is we want a pluripotent response," Frieden said. "That means sustained funding for health organisations within the U.S. government, including the CDC. which means full support for the globe Health Organisation, both in terms of funding and mandate, which means a far better, stronger approach to identifying and fixing the gaps in readiness round the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment