Last year, archaeologists presented an incredible first: the discovery of a mummified fetus within the abdomen of its mummified ancient Egyptian mother.

Who the woman was, and how she died just over 2,000 years ago are both still mysteries – hence she is known as the Mysterious Lady. But now we know how the fetus was preserved. According to new research by the Warsaw Mummy Project, the preservation occurred via the acidification of the woman's body as she decomposed.

As the researchers so colorfully put it, the process is akin to pickling an egg.

"The fetus remained in the untouched uterus and began to, let say, 'pickle'. It is not the most aesthetic comparison, but conveys the idea," the research team, led by bio-archaeologist Marzena Ożarek-Szilke of the University of Warsaw in Poland and archaeologist Wojciech Ejsmond of the Polish Academy of Sciences, explain in a blog post.

"Blood pH in corpses, including content of the uterus, falls significantly, becoming more acidic, concentrations of ammonia and formic acid increase with time. The placement and filling of the body with natron [a salt mixture collected from dry lake beds] significantly limited the access of air and oxygen. The end result is an almost hermetically sealed uterus containing the fetus."

The question as to whether what they had found was actually a fetus was posed by radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University in Egypt, who penned a reply to the initial discovery. She noted that no bones could be detected in the scans of the mummy, and therefore the identification of a fetus must be inconclusive.

But this is not unexpected, Ożarek-Szilke and her team argue. Fetal bones are very poorly mineralized during the first two trimesters, which means they are difficult to detect in the first place after undergoing taphonomic (or preservation) processes. Fetal bones are even hard to find during archaeological excavations.

In addition, the acidifying processes that would have taken place inside the corpse of the Mysterious Lady as her body decomposed would have further demineralized the already delicate fetal bones.

It's not dissimilar to the natural process of mummification that takes place in peat bogs, where the highly acidic environment 'pickles' soft tissue, but demineralizes the bones.

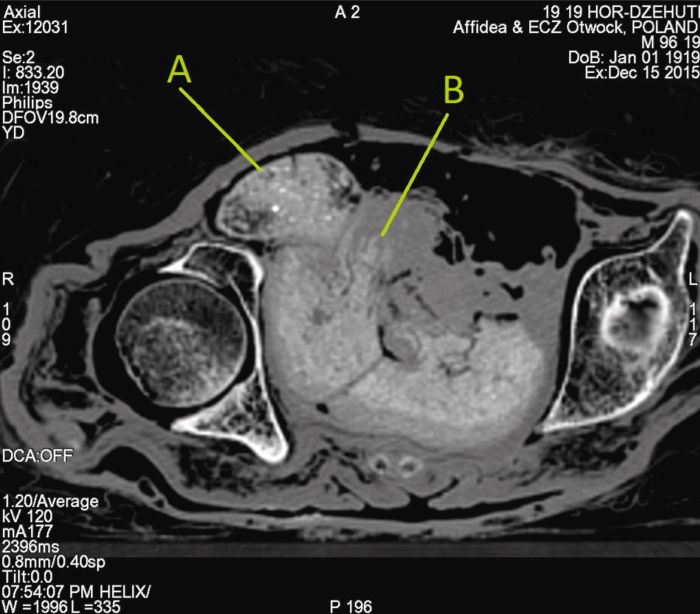

CT scan of the fetus in utero; A is the head and B is the hand. (Ejsmond et al., J. Archaeol. Sci., 2022)

CT scan of the fetus in utero; A is the head and B is the hand. (Ejsmond et al., J. Archaeol. Sci., 2022)

"This process of bone demineralization in an acidic environment can be compared to an experiment with an egg," the researchers write. "Picture putting an egg into a pot filled with an acid. The eggshell is dissolving, leaving only the inside of the egg (albumen and yolk) and the minerals from the eggshell dissolved in the acid."

The reason the body of the Mysterious Lady and the body of the fetus are different in this regard is because they mummified differently. The Lady was mummified using natron, a naturally occurring salt mix that the ancient Egyptians used to dry out and disinfect bodies. The fetus, in her sealed womb, mummified in the resulting acidic environment.

In addition, the minerals leached from the fetus' bones would have been deposited in the soft tissues of the fetus itself, and the uterus around it, resulting in a higher-than-expected mineral content. This means that these tissues would have higher radiodensity in the CT scans.

The results suggest that perhaps other pregnant mummies might be hiding in plain sight in other museum collections. Scans of mummies are usually identifying bones, and amulets tucked inside their wrappings. By looking carefully at soft tissues, other such mummies might be identified.

In turn, this might help archaeologists and anthropologists uncover why the fetus was left intact when the Mysterious Lady's other internal organs were removed for the mummification process.

"Maybe it had something to do with beliefs and rebirth in the afterlife," Ożarek-Szilke told Science in Poland. "It is still difficult to draw any conclusions as we do not know if this is the only pregnant mummy. For now, it is definitely the only known pregnant Egyptian mummy."

The team's analysis also determined that, due to the position of the fetus and the closed condition of the birth canal, the woman did not die in childbirth. Previous analysis found that the Mysterious Lady was between the ages of 20 and 30 when she died, and her pregnancy was between 26 and 30 weeks.

"The Mysterious Lady died together with the unborn child, and by examining her, we restore their memory," the researchers write.

"We remember that it was a long-lived person who had her dreams, probably loved ones and was loved. Now she reveals to us the secrets she took with her to the grave."

The research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

No comments:

Post a Comment