When a dog-sized Psittacosaurus was living out its days on Earth, it was probably concerned with mating, eating, and not being killed by other dinosaurs. It would never even have crossed its mind that, 120 million or so years later, scientists would be peering intensely up its clacker.

However, that's precisely what scientists did, publishing in 2021 an exquisitely detailed description of a non-avian dinosaur's cloaca: the catch-all hole used for peeing, pooping, mating, and laying eggs.

This Swiss Army knife of buttholes is common throughout the animal kingdom today – all birds, amphibians, reptiles, and even a few mammals possess a cloaca. But we know little about the cloacae of dinosaurs, including their anatomy, what they looked like, and how the animals used them.

"I noticed the cloaca several years ago after we had reconstructed the color patterns of this dinosaur using a remarkable fossil on display at the Senckenberg Museum in Germany which clearly preserves its skin and color patterns," paleobiologist Jakob Vinther of the University of Bristol in the UK explained last year.

"It took a long while before we got around to finish it off because no one has ever cared about comparing the exterior of cloacal openings of living animals, so it was largely uncharted territory."

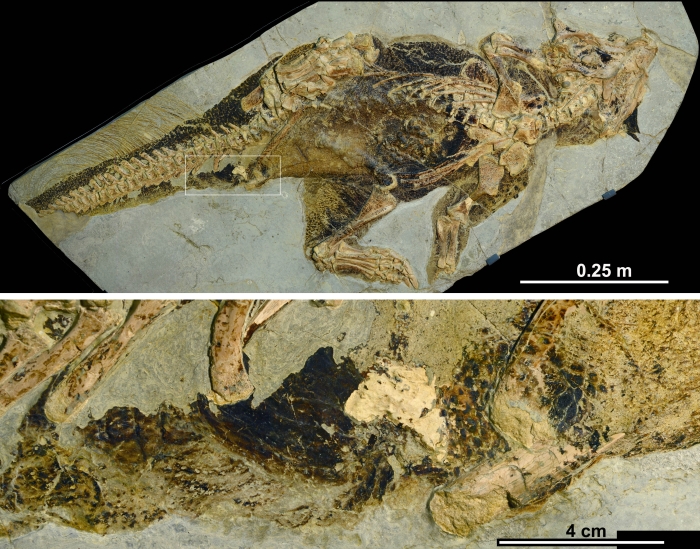

The Psittacosaurus specimen. (Vinther et al., Current Biology, 2020)

The Psittacosaurus specimen. (Vinther et al., Current Biology, 2020)

So that's what the team did, comparing the fossilized cloaca to modern cloacae.

Their specimen was the only non-avian dinosaur fossil known to have a preserved cloaca, but due to the way the fossil was positioned, the internal anatomy of this opening has not been preserved; only the external vent is visible. This means there was a lot of information the researchers couldn't gauge.

"We found the vent does look different in many different groups of tetrapods, but in most cases it doesn't tell you much about an animal's sex," said anatomist and animal reproductive system expert Diane Kelly of the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

"Those distinguishing features are tucked inside the cloaca, and unfortunately, they're not preserved in this fossil."

Even so, that exterior anatomy could contain some pretty interesting clues as to what some dinosaur cloacae looked like, and how they were used.

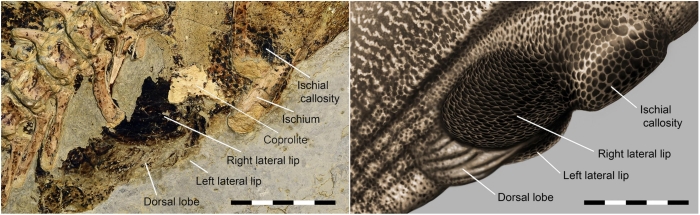

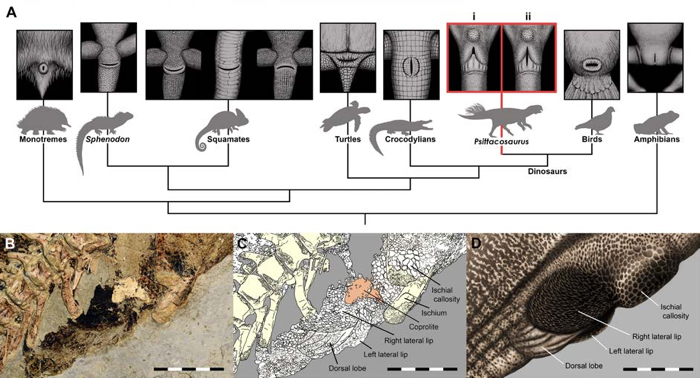

Although the dinosaur's cloaca is unlike any other known modern animal, the team was able to identify several features in common with crocodilian reptiles, such as alligators and crocodiles, and birds.

There was a dorsal lobe that seemed similar to the cloacal protuberance seen in birds – a rounded swelling near the cloaca during breeding season, where the male stores sperm – although, again, without the internal anatomy, it's impossible to say for sure.

Secondly, the cloaca had lateral lips on either side of the opening, much like those of crocodilians. Unlike crocodilians however, Psittacosaurus had them arranged in a V-shape, thus the opening could have been slit-shaped; it also could have been round, like in birds.

(Jakob Vinther, University of Bristol and Bob Nicholls/Paleocreations.com 2020)

(Jakob Vinther, University of Bristol and Bob Nicholls/Paleocreations.com 2020)

Above: The cloacal vent, and how it might once have looked.

Other features, however, were also similar to crocodilians. The cloacal lips were covered in small, overlapping scales and heavily pigmented with melanin. In crocodilians, these lobes function as musky scent glands that are used during social displays – a function, the researchers said, that would be supported by the heavy pigmentation.

"As a paleoartist, it has been absolutely amazing to have an opportunity to reconstruct one of the last remaining features we didn't know anything about in dinosaurs," said paleoartist Robert Nicholls.

"Knowing that at least some dinosaurs were signaling to each other gives paleoartists exciting freedom to speculate on a whole variety of now plausible interactions during dinosaur courtship. It is a game changer!"

Because only one fossilized cloaca has been recorded, it's impossible to tell whether the display may have been sexual, and whether the fossilized dinosaur is male or female. But the colorful lobes could hint at the shared ancestry between birds and non-avian dinosaurs, the researchers noted in their paper.

Comparison of different cloacae. (Vinther et al., Current Biology, 2020)

Comparison of different cloacae. (Vinther et al., Current Biology, 2020)

For lack of samples, this is a very understudied region of dinosaur anatomy, and only by examining a wide range of dinosaur cloacae can we learn more about how they functioned in the social and reproductive lives of these ancient animals.

No doubt, other paleontologists are on the lookout for fossilized buttholes to try to fill this gap in our understanding of dinosaur life.

No comments:

Post a Comment